Witch, wild woman, and angry, vengeful goddess – images of women’s power, society, rage and sexuality appear in every culture around the world. In contemporary Western culture, the lesbian-feminist represents this archetype. When big, tough, hairy, ugly, angry lesbian separatists work for women’s freedom, we inherit and preserve this vital legacy.

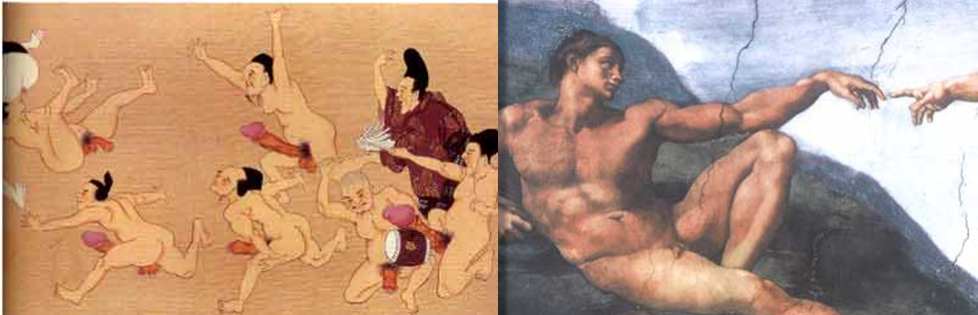

Hans Baldung Grien, Witches’ Orgy, 1514, drawing

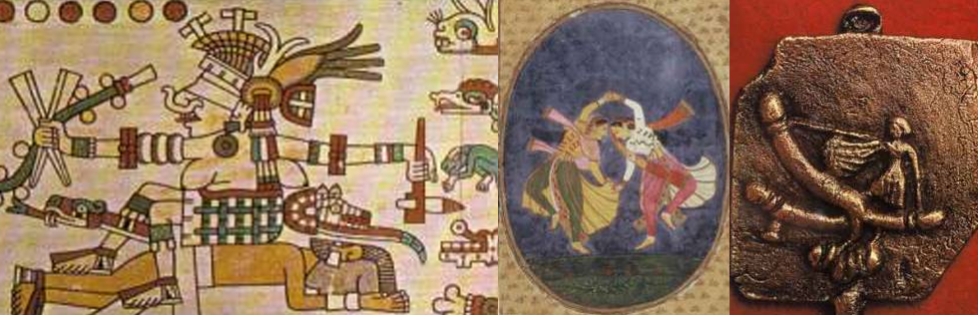

In Ancient Greece, the Furies rage against a matricide. In the Mexican-American desert, La Loba, Wolf Woman, assembles bones and sings them into life. In the Arctic the Inuit goddess Sedna lives at the bottom of the sea, fiercely guarding all the creatures she gave birth to. In India the goddess Camunda dances in the cremation grounds, eating corpses. Her hunger can never be satisfied, and she fills the world with her terrible cries.

In Europe during the Inquisition women who did not repudiate this archetype were tortured and burned. Judy Grahn writes, “they don’t have to lynch the women / very often anymore….”:

“The European witch trials took away

the independent people; two different villages

– after the trials were through that year –

had left in them, each –

one living woman:

one”[1]

Women internalize the damage, supervise and police themselves, and limp through the world with injured instincts. Lesbians create a radical alternative. We prefigure a society outside the patriarchy’s order and boundary, constituted through desire, empowered by anger, aligned with animals, and informed by the wild.

Shadow: Lesbians may be the foremost providers of liberating services to women, but lesbians are not women. Monique Wittig argues that “woman,” like “slave,” is a concept that cannot be rehabilitated. It has meaning only in heterosexual systems of thought and heterosexual economic systems.[2]

Related Figures and Attributes: Angry, Wild Man, Abnormal, Victim

For more writing on this symbol, see these chapters of Orientation: Mapping Queer Meanings: Rage, The Sea, The Body

[1] Judy Grahn, The Work of A Common Woman, New York: Crossing Press, 1978, (119).

[2] Monique Wittig, 1993, (32).