Bronze Amulet from Suffolk, England, woman wielding a triple phallus

Bronze Amulet from Suffolk, England, woman wielding a triple phallus

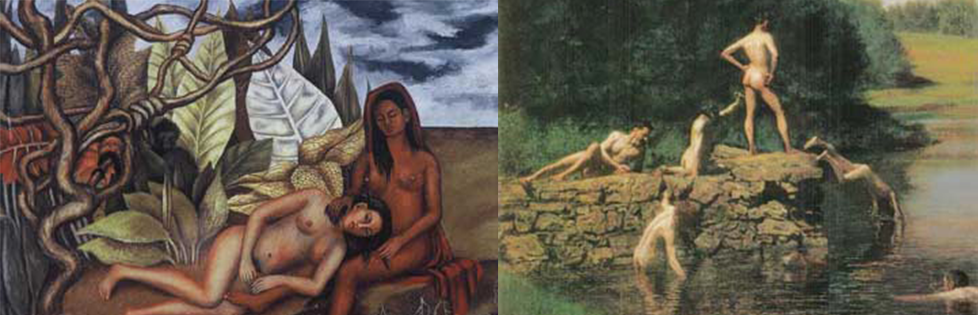

A queer body is more than an assembly of organs and physiological functions. It is an anomaly, a mystery, a metaphor.

Ordinary human bodies are transparent to their medical certainties. In the mechanistic world-view of modern science, questions about the meaning of life are answered by the body’s reproductive functions. Queer bodies refer us to the mystery of origin. What makes us? Why are we here?

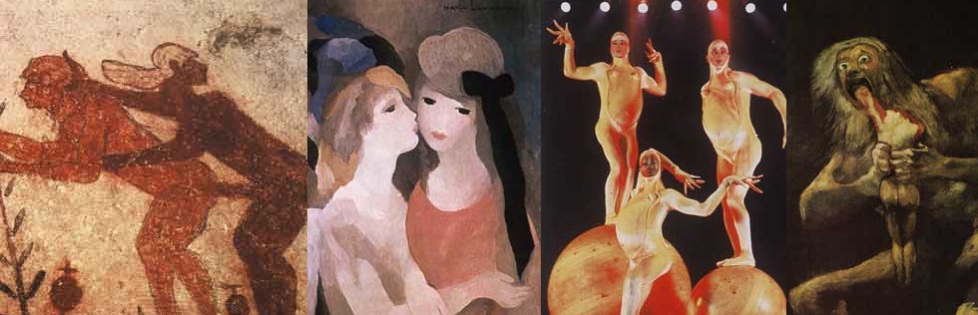

Queers cannot automatically assume a gendered body. We have no way to unproblematically “be” men and women. Homosexuality means always flirting with cultural stereotypes, performing gender, and de-naturalizing it. We call the assignment of gender categories into question.

A gay man can assume the clothes and gestures of a woman, but he does not become a woman. Judith Butler observes that drag queens mimic the “structure of impersonation by which any gender is assumed.”[i] When a drag-queen sings the feminist anthem “I Am Woman,” we laugh at how a woman is contrived. Gay men can also act masculine, but this masculinity appears in a way that again calls gender categories into question. In gay men, masculinity loses its punch. The forms and objects of masculinity stop reading as expressions of power and privilege, and instead become erotic lures. Through gay performances of masculinity, we notice that every man contrives his gender through donning the clothes, postures and privileges of men. All men become visible as male impersonators, acting out the naturalized ideal of what a man is.

Yoruba mask of a woman giving birth, worn by male dancers

A butch lesbian can likewise assume the clothes and gestures of a man. She can be seen as “masculine,” she looks so powerful, visible and authoritative. A femme lesbian dresses in a skirt, lipstick and high-heeled shoes. She looks almost like an ordinary woman. But lesbian culture understands the butch-femme relationship with gender as creative and complex. Joan Nestle describes femmes and butches as “gender pioneers with a knack for alchemy.”[ii] While men and women are impaled on opposite poles of sexual difference, butch-femme is “a lesbian-specific way of deconstructing gender that radically reclaims women’s erotic energy.”[iii] Gender is posed as a space of seduction, play and invention.[iv] Butch Jan Brown comments, “We become male, but under our own rules. We define the maleness. We invent the men we become.”[v]

An ordinary man or woman undertakes gender as a compulsive and compulsory repetition of the “fact” established at birth. The first words spoken of any baby describe their destiny. “He’s a boy!” “It’s a girl!” One might be a little more or a little less like the stereotypes; no one feels adequately identified by them. The assumption of gender involves impersonating an ideal that no one really inhabits, as Judith Butler says.[vi] The butch undertakes gender differently, making her body into a metaphor. She is steel strong and rock hard. She stands for courage, daring, ferocity, the truth of independence, the dream of power. She does not (cannot) become a man in the social and symbolic order. She can only be a sign, a symbol, an aperture opening into the archetype of masculinity. Beside or inside the butch there is always also the femme. The femme does not aspire to be (and cannot be) a woman in the social and symbolic order. She is an outlaw. Because of who she loves, she must be impossibly strong, resilient, radical. Yet she uses femininity as a language with which to represent herself and her desire in erotic relationships. Femme is a symbol of vulnerability, helplessness, the truth of dependence, the dream of surrendered skin. Butch-femme is a way of being that gives weight and resonance to the erotic moment. When we are held in one another’s arms, power and surrender can be soul-gifts, not compulsions of class and gender. Courage, compassion, ferocity, tenderness – capacities so profoundly engaged in the erotic moment – are translated into a stance, a relationship, and a subculture. Butch and femme suggest the possibility of life before or after gender – open to the archetypal patterns expressed by male and female, without capitulation to the social designations and compulsions. Being queer, we are called to live with the granite endurance of Stone Butch and the glittering diamond of High Femme, combined in our psyches and relationships.

Double phallus forms, in a convenient size for lesbian sex, are among the oldest artifacts found throughout the world. This dildo from ancient France is carved with vulvaforms. It invites us to imagine gender as a plaything that can be slippery and skillfully employed.

Double phallus made from deer antler, engraved with vulvaforms, ancient France

Many other lesbians choose neither butch nor femme. Rather than building an interrogatory, erotic or playful relationship with gender, we can seek to refuse it. Saying ‘No’ to the social, legal and physical consequences of being a woman, lesbians can become “embodied” in a profound sense that is unavailable to non-lesbian women. We can cultivate our body hair, use our muscles, and wear comfortable shoes. This is a way of refusing to be a woman, refusing the form of a woman’s body that our culture demands. It is also a positive claim to strength, fur, comfort, and lesbian visibility. Inhabiting our big, tough, hairy bodies with persistent grace, we embody capacities and autonomies no ordinary woman can dream of. Women who are not lesbians find their bodies made into the preserve of medical knowledge. Internal and external appearances are anatomized, defined, scrutinized, diagnosed and regulated by biomedical, pharmaceutical and cosmetics industries. Women’s identities devolve to their reproductive organs, and these are considered the business of every passing stranger, the husband, the state, the doctor, the pro-life movement, the pro-choice movement. Barbara Duden comments, “woman’s body is public space.”[vii] Lesbians disappear from the equation, slip away from the scrutiny, and then return shrieking complaint – we are invisible! Outside the reproductive imperative, refusing the clothes, gestures, roles and functions that define and confine what a woman is, we are ignored by the vast machinery that produces women. We are not seen, diagnosed, and adjusted by expert knowledge. We are cast upon our own resources. Thanks to double-edged sword of lesbian invisibility, we can assume a private life and feel our bodies as private space in ways no ordinary woman can. Lesbians can suffer without being fixed. We can feel anger and enjoy laughter viscerally and unapologetically. We can have sexual pleasure without concern for pregnancy. Lesbian bodies, as spaces of physicality claimed apart from expert knowledge, can admit embodied emotions.

We may choose to approximate women or to impersonate men, but as lesbians we always dwell in a nether-world of neither-nor. In Herbert Marcuse’s phrase, we are “the continuous negation of inadequate existence.”[viii] Being what a woman is not instead of always only what she is, we confront the totalitarian regime of the given facts with what is excluded by it. If woman’s autonomies and capacities ever find space to exist, it will be in bodies built by lesbians.

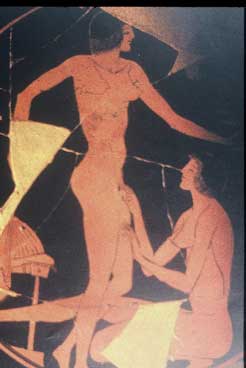

Greek painted pottery, two women, 5th C BC

[i] Judith Butler, in Diana Fuss, ed., (21), emphasis original.

[ii] Joan Nestle, 1992, (14).

[iii] Joan Nestle, 1992, (14).

[iv] This paragraph in particular and this chapter in general owe much to Sue Ellen Case, “Toward a Butch-Femme Aesthetic,” in Abelove et. al. (1993), p. 294- 306.

[v] Jan Brown in Joan Nestle, ibid., (414).

[vi] Judith Butler in Liz Kotz, 1992, (85).

[vii] Barbara Duden, 1993.

[viii] Herbert Marcuse, 1960.