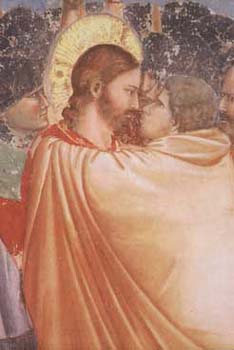

A thirteenth-century tile from Chertsey Abbey, England, showing King Mark kissing his nephew Tristan.

A thirteenth-century tile from Chertsey Abbey, England, showing King Mark kissing his nephew Tristan.

Saint Augustine, the Father of Christianity whose contempt for same-sex passion helped shape Christian intolerance, once loved another man. Augustine was devastated when his lover died. Torn apart, in unbearable pain, he turned to the Christian god. After his conversion Augustine came to regret the sexual aspect of his relationship, writing “. . . I contaminated the spring of friendship with the dirt of lust and darkened its brightness with the blackness of desire.”[i] Augustine shaped his pain and shame into a weapon. It is still a danger. Betrayal, self-loathing, revenge, the Judas kiss – alongside all the miracles and wonder of queer existence, these destructive patterns persist. How do people who have been so thoroughly associated with evil learn to be good to themselves and each other? With no sense of what is good and right that can embrace us, we can be demoralized. We can stay trapped in self-hatred and internalized homophobia. We can be deprived of spirit, courage and kindness. Or homosexuality can lead us through the fire, to a deeply ethical, yet radically open, way of living in the world.

Ethical behavior is traditionally based on obedience to a code of rules that defines virtue and prohibits vice. For centuries this code has been contrived and derived from gender. A “good woman” and a “good man” are she and he who emphatically disavow a capacity for destabilizing the “natural functions” of their sex. The very word “bad” is derived from the Old English bœddel – a derogatory term for sodomites.[ii] As queer people, we practice the very possibilities that are prohibited by society’s implicit and explicit ethical norms.

It is a dangerous transgression. Shame yawns greedily, ready to devour us. How many queer people internalize a sense of wrongness? Today any queer community newspaper contains advertisements from straight-looking, straight acting gay white men seeking same – a mirror image to confirm self-hatred and contempt for queer potentialities. How many of us are lost to self-loathing, fear, humiliation, failure? We succumb to failure of nerve – we cower. We make up a new set of rules delimiting virtue and vice, and use them to punish one another.

As well as an abstract set of rules we cannot follow, ethics is a set of concepts we can scarcely do without. But ethical concepts like “integrity,” “honesty” and “altruism” may presume a different sense of self and world than queer people can attain. When boys and girls grow into men and women with opposite-sex attachments, they are confirmed at every turn by culture and society. The rites and rituals of opposite-sex dating, mating and marriage confer them place and status in the human community. Boys and girls who aspire to same-sex passions and attachments develop a very different sense of self and world. Dorothy Allison writes, “by the time I understood I was queer, that habit of hiding was deeply set in me, so deeply that it was not a choice but an instinct.”[iii] We stay hidden, isolated and invisible, or become hyper-visible – as heroes, clowns and victims – roles and offices that are just as lonely and claustrophobic as the closet. The self is incarcerated with secrets and burdened with shame. The yearning to know and be known is frozen and entombed.

How does anyone who grows up queer imagine they have integrity – that they are pure, unbroken, untouched, whole? Honesty means we will not survive; disguise and dissimulation are prerequisites to our existence. And altruism – devotion to the interests of others – is just as impossible, when becoming who we are is what offends. Capacities for moral agency derive from a strong sense of self and engagement with the human community. Queer people grow up deprived of both. We are each torn apart and town away from the social fabric. How then can we develop capacities for ethical behaviors and moral choice?

We can craft and practice an ethics that is informed by the peculiar experience of being queer. The enterprise requires a more complex sense of self and one’s engagement with the human community than traditional ethical concepts can presume. For queer people, the self is a locus of possibility, a place of action and change that subverts the social order. This order is heterosexuality; heterosexuality consists of the conventions, rules and economic relationships that form the social environment. Monique Wittig writes of how, one by one, lesbians break the social contract. In our voluntary associations with one another, we imagine a new form of social bond. Wittig writes, “. . . If ultimately we are denied a new social order, which therefore can exist only in words, I will find it in myself.”[iv] This is not the form of self envisioned by contemporary psychology as a locus of private meanings and unique characteristics withheld from social life. Queer people encounter themselves as something else. Our most intimate passions and personal pleasures invent an outer world that is not yet possible.

We envision social transformation desperately, with our desires, and we envision it playfully, with style. Lesbians in lipstick or lumberjack shirts, gay men in leather or crinolines – the self we present to the world is not self-evident. Style takes the self as a work to be accomplished. Following Michel Foucault, we can see self-fashioning as an opening for creative life.[v] Inventing, costuming, practicing and staging the self, we make a tiny space within the apparatus of power where choice is possible. Being queer is itself an ethical practice; we use our sexuality to craft forms of self and relationship that exceed the evident unfreedoms we inherit.

A complex sense of self, forged in social transformation and self-invention, informs an ethics that is peculiarly queer. For GLBTQ people, goodness does not arrive through silence and self-sacrifice. We gain strength and voice from others’ strength and voices. We give space to others when we invent and present ourselves. A queer form of altruism requires neither obedience nor subservience. Living for others is a creative choice, emerging through passions and pleasures. Living for self is not about winning power over others. It means using one’s singular voice, across its entire range, to sing the world to life. Care of an unstable, invented self is a key to a rich, multifaceted community, where new kinds of relationships become possible through being queer.

Ethics is visible not only as a code of rules or a series of concepts governing individual behavior. Ethics also consists of the moral climate, the ethical atmosphere of public discourse and institutions. It is this ethical environment we address with the pursuit of political equality for queers. We seek the decriminalization of homosexuality. We want protection from discrimination in housing and employment. We lobby and litigate for an education system that stops terrorizing queer youth. We want the right to marriage and its attendant privileges. Underlying our demands is a passion for justice. And there is a danger. The effort to convert homosexuals into entitled participants in the democratic process can tempt us to renounce our peculiarities. Representing ourselves as a group or category “deserving” equal rights can mean disguising and denying queer difference.

There is a tension between GLBTQ people who seek respect and tolerance for their private passions, and those who see radical meaning in queer difference. On the one hand, respectable queers are the ones who find acceptance and forge alliances. They work patiently to create incremental social change. Eric Clarke cautions that contemporary social tolerance of gays and lesbians effects “the transformation of political aspiration into managed inequity. Tolerance is the ruse by which respect for difference covers over a legitimated disrespect. . . .” [vi] To be assimilated, homosexuality must be erased, desexualized and silenced. After a long battle by queers and allies in the church, the Anglican Diocese of New Westminster (Greater Vancouver) passed a resolution in June 2002 permitting (not compelling) parishes to celebrate same-sex unions in quasi-marriage ceremonies. Queer Christians rejoiced. But there are dangers in normalizing our existence. Acceptance comes only at the cost of disavowing morally unworthy – or queer – sexual practices and identities. Commentator Davis Harris writes urging tolerance in a National Post article (June 22nd 2002) titled “Gay Unions Shouldn’t Divide the Church.”: “The blessing of gay unions should help bring stability to gay relationships. This, in turn, should reduce the spread of various diseases which have a high economic, as well as social cost.” Nothing has challenged his negative stereotypes of homosexuality. Yet he promotes acceptance, with the view that through adherence to a heterosexist paradigm we might be de-queered. Deprived of the complex network of allusions and associations that compose his image of (unstable, diseased) homosexuality, we might become almost the same as anyone else. “Good” queers are divided from “bad.” Those who can be recuperated to sameness are separated from those who persist in difference. Even the act of granting grudging acceptance to some queers creates and upholds negative stereotypes of homosexuality, while saying that some righteous GLBTQ people do not conform to them. Conformity is a precondition for public presence. Our difference cannot make a difference. Queer rights in this sense require submission to moral regulation that pits us against one another, and against our own capacities for myth and meaning.

Giotto, The Judas Kiss, detail of fresco, 1305

Same-sex passions flourish, at all times, in all conditions, no matter what punishments and permissions await us. Our capacity to live despite the absence of an environment of justice affords telos – purpose – to queer existence. We are called to create a world where there is safety and security for all of who we are. The ethical environment that homosexuality predicts values equality and not equivalence. Enfranchisement cannot derive from conformity to approved behaviors. Instead, we can invent a sociality where difference makes a difference. Being good can become as multifaceted and fabulous as being gay.

Queer is deeply suspicious of any moral stance. Our suffering and exile are evidence that conventional morality is bunk. The moral climate supports hierarchy and exclusion while paying lip service to democracy and belonging. Virtue is a ruse that makes slaves content to serve. Values alibi inequities. This kind of cynicism at least can free us from the endless treadmill of seeking acceptance. No longer constrained by a need to fit in, we can fly out, and explore the far reaches of queer identity. There is a danger. When we care less, we could be careless. Exiled from the moral majority of fools and bullies, we could pretend to self-sufficiency, admit to needing nothing at all. But if we pretend not to ask and refuse gratitude for the crumbs we are given,[vii] we fail to live the paradox of dependence and independence. We cannot be fully independent until we are enmeshed in and supported by a community. We achieve an altruism of living-for-others when we speak for and through our uniqueness. And it is when we give ourselves away in love and community that we come alive to our selves.

Homosexuals are forced to exile, suffering and solitude. We can use these experiences to become careless or de-moralized. Or we can use them to craft a beautiful life, following a path of deep humility. If we are humble, we are willing to receive, to ask, and to learn. We accept change; we are open to a multiplicity of meanings and functions. We are incomplete; we acknowledge need and dependency. We receive and give thanks. This humility queerly leads us to strength and pride. Through humility we become neither powerless victims, nor arrogant self-seekers. Instead we are singular members of a community. In community we share our gifts. We use our desires to weave a world of meaning, where each of us can find the responsibilities and commitments that lead to lasting joy.

[i] Confessions 3.1, quoted by Boswell, 1980, (135).

[ii] John Ayto, 1990 (48).

[iii] quoted in Nealy, 1995, (Sept. 1).

[iv] Wittig, 1992 (45).

[v] See Halperin, 1995, (73-77).

[vi] Eric Clarke, Virtuous Vice: Homoeroticism and the Public Sphere, (Durham: Duke University Press, 2000), quoted by Lisbeth Lipari, 2002, (170).

[vii] Thomas Merton, 1956, writes: “True poverty is that of the beggar who is glad to receive alms from anyone, but especially from God. False poverty is that of a man who pretends to have the self-sufficiency of an angel. True poverty, then, is a receiving and giving of thanks.” (94).