China, Two women with bound feet having sex outdoors, silk painting, 1640

China, Two women with bound feet having sex outdoors, silk painting, 1640

“The country that enters us through the language and tongue of a lovher is a country that unites us. The country that enters into us through the beauty of trees, the fragrance of flowers and the shared night is a country that transforms us. The country that enters into us through male politics is a country that divides us. The country that enters into us like dreaming into life is a country that invents itself.”

– Nicole Brossard[i]

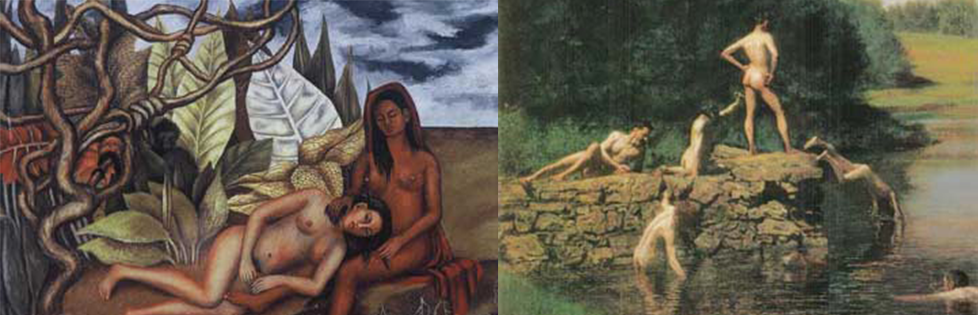

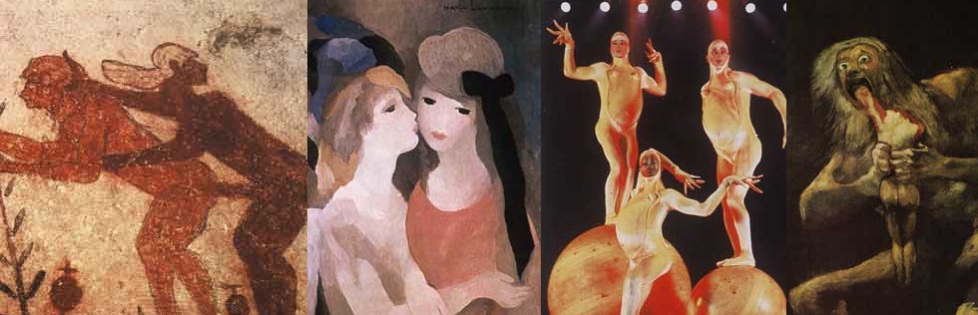

We dream of another country, where we can be homosexual. The name Lesbian carries this dream. We are citizens of an imaginary country on the Mediterranean Sea, where love between women exists in profusion, in the open air, sun-washed and bright. Lesbians everywhere approximate this utopia with whatever resources we can muster. From the Ladies of Llangollen[ii] to the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival, lesbians make lesbian space. New rules of engagement; a different history and culture; a transformation of temperature; the unimaginable opening of possibility: another country “enters into us like dreaming into life.”

The country we are born into, or that Brossard says “enters into us through history and its violence,”[iii] has no space for these fabulous myths and meanings. Heterosexist assumptions about gender and sexuality structure the physical world. Every existing physical space is simultaneously an ideological space that precludes the existence of queer people. Zoning bylaws enforce the difference between (men’s) space for work – the city with its phallic buildings – and (women’s) space for living – the suburban home with its cuntlike enclosures. It is impossible to “be” queer in the ideological space of a house. Private homes stink of family life, with all its prohibitions and exclusions. The design of buildings enforces equivalence on all family units, however structured. One cannot “be” queer at work, where sex is not supposed to happen and sexual identity can at best have no meaning or consequence. Nature is produced as an ideological space that proves homosexuality is impossible. City streets are redolent with past and present dangers. The soul of the citizen – worker, voter, universal soldier – may include a predisposition to homosexuality, but there is no space on earth where queer can come to characterize our lives.

In another country, homosexuality is the heart of the matter. The many projects and meanings we are called to – from intergenerational passion to frivolity and innocence – need space to be. Space-making is a primary project for queer people. Without space, we cannot survive.

The Ladies of Llangollen, (Sarah Ponsonby and Eleanor Butler), engraving based on an oil painting by Mary Parker, c. 1795

Utopia is the only place where being queer is completely possible. This picture of the Ladies of Llangollen, in their butch clothes, at home in their library, evokes a world for women that can include love of learning, freedom of movement, and a voluntary relationship of equal partners. Walt Whitman writes:

“I dreamed of a city where all the men were like bothers,

O I saw them tenderly love each other –

I often saw them, in numbers,

walking hand in hand;

I dreamed that was the city of robust friends –

Nothing was greater than manly love –

it led the rest.”[iv]

He evokes a world for men that can include tenderness, loyalty, and open affection. These are utopian visions, homeless in the world we know. Each time we represent ourselves and our desires in public language, visual culture, personal space and social relationships, we make an opening, a passageway that leads to another country where there is space for us.

A queer house can be such a passageway. From the outside, it looks the same as any other single-family dwelling. Economically, it functions just like any other. But inside the house where two men or two women share their lives, the house holds densely-layered meanings and utopian visions.

Each queer house is a sanctuary. The walls of the house describe the limits of what enclosed, controlled and private space we can wrest from a dangerous world. Inside, we create a sacred space of permission and safety. Here, wildlife can take refuge. We create home in a profound sense, a place of belonging.

Queer space is filled with conversation. Design and atmosphere encourage talk. Queer people cannot silently assume a place in a world that exists without them. Conversation constructs identity, community, self-knowledge, and personal space. Words create worlds.

Each queer home employs the metaphor of the closet. Aaron Betsky writes, “The closet is the architectural equivalent of the Freudian mind. It is the hidden interior where we construct ourselves.[v]” Heterosexist space represses this symbolism by inserting coherent passages between inside and outside, an awful continuity between private and public life. Queer space honors interiority with difficult entryways, high thresholds, gradations of intimacy, the judicious disclosure of secrets. The difficulty in representing ourselves as queer in public language and social relationships creates space and distance. Individuality can be refined in space that hides an undisclosed self.

Elemental images, patterns and archetypes resonate through queer space. Wherever possible, queer homes seem to confirm and evoke the power and meaning of the elements. Fireplaces and candles bring sacred fire into our living rooms. Beds – symbolizing fire while heterosexual beds symbolize breeding – are shrines. Rich and abiding contact with water – in pools, ponds, elaborate bathrooms, views, tubs, drinking water – brings unconscious life, and our kinship with all life, on site. Connections with the earth are created by gardens, indoor flowers and plants, decks, entryways and openings that bring the outside in and the inside out. Personal decoration, artifice, and the pleasure we take in making things beautiful, give us air to breathe, just as conversation does. Heterosexist space boxes in and flushes away the world’s elemental rhythms. Living queer, we find the wild world confirms and creates us. Making space for intimate and repeated contact with the elements, we are invited to the full dimensions of our lives.

Restaurant mural, Florence, 2002

Every queer space opens into the community. The utopian dream of a beloved community is the heart of queer space. House opens to neighbourhood, watershed, ecosystem, globe – and a universe governed by the great gay principles of unity, diversity, equality, celebration, unconditional acceptance, joy. The community is marked on a mental map carried by every queer person. Interconnected maps chart a vast network of places where we are welcome, where we have the power to participate in community affairs, where we can hold hands with our lovers, where we can dance. The territory goes around the world: in any city, in any country, there will be places where we are welcome because of our sexual orientation. Being queer, we have the right and the responsibility to enter the community, to dream it and to build it into our homes, our friendships, and our public life.

Queer houses provide home, a space of belonging. They encourage conversation and friendship. Engaging the metaphor of the closet, they support rich and complex individualities. They put us in touch with the elements, connecting us with nature and magic. Opening to the community, they fill us with possibility and love. Queer space challenges and empowers us.

Heterosexist houses impose a superficial order and conformity on the gender drama seething beneath the surface. These houses repress change. They render individual difference meaningless. Men and women relating to one another in the heterosexist space of the single-family dwelling are boxed in, isolated, silenced, held apart from nature and community. Whatever change they can achieve in private space is without consequence in social space and public life, where the institutions and customs that regulate gender subsume their voices and their identities. They lack a door and a pathway to another country.

Queer space creates this opening to another country. Envisioning and approximating a comfortable, gracious, healing and connected world, our homes can suggest Utopia. Another country “enters into us like dreaming into life,” challenging the prevailing order in our hearts and imaginations. If another country is unimaginable, we can have no coherent view of the changes we desire. However dissatisfied we are with the state of things, we stay stuck in self-interest, or we seek small improvements and parochial reforms at great cost, with little benefit. Queer homes – tiny city apartments, lesbian communes, spacious country estates, even jail cells – can help us find and hold an alternate world view. Another country is a place where women ride wild horses. Men can be soft and pliant. Nature looks like us. Houses are opened to multiple meanings and functions, intersexual and intergenerational. Cities are magic concentrations of energy and light. Work and love are connected, intricately and intimately, when what we make is not severed from who we are, or can become. The world we envision – with candlelight, a meal for friends, photographs on a wall, a secret cherished – involves gigantic change, the broad social and economic reorganization of society.

Herbert List, Ostee, 1933

Radical envisioning requires space and place. When we hold a sense of the world we want, we can begin to let go of the world we know, despite its demands and urgencies. In small ways, limited and constrained by virtually everything, each queer person can make a home, or an image of home, that empowers broad social change. Entering queer space, we are guided to find, claim, and at last to create a world that is sweet and bold enough for us.

[i] (sic). Nicole Brossard, “Green Night of Labyrinth Park,” trans. Lou Nelson, in Betsy Warland, ed., 1991, (197).

[ii] Lady Eleanor Butler and Sarah Ponsonby set up house together in Wales in 1778. They lived together in Llangollen for fifty years, hosting many distinguished guests and becoming famous in England for their independent life, their manly attire, and their devotion to one another.

[iii] ibid., (197).

[iv] Walt Whitman, 1860, Bowers, ed., (114)

[v] Aaron Betsky, 1997, (59).