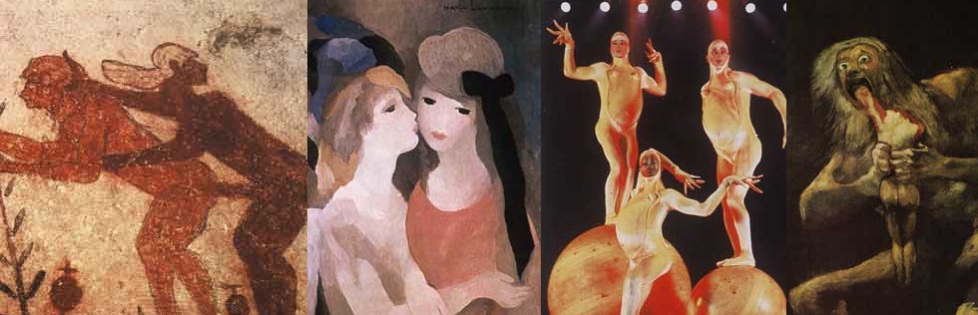

Man with Centaur, metal statuette, possibly early 8th century BC.

Man with Centaur, metal statuette, possibly early 8th century BC.

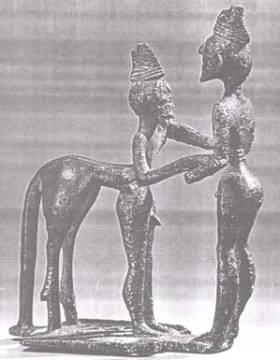

With dawn breaking over the Mall in Washington, four eight-person teams began carefully unfolding twenty-four square-foot quilts, each containing thirty-two panels. One person after another stepped up to the microphone, each reading a list of thirty-two names. When the 1987 ceremony was finished, 1,920 memorial panels covered the earth. Between Washington’s phallic monuments to power and the war dead, the soft, bright, handmade memorial to gay men dead of AIDS evoked, for a moment, the impossible enormity of loss.

Being queer is characterized by such acts of creating place. We build temporary, provisional and transgressive space in which homosexuality is possible. GLBTQ people have to continually, self-consciously make space in which to exist. Queer space is no sooner built than it disappears: folded up and put away; ghettoized; annihilated by violence; absorbed by the vast and overwhelming silence of heteronormative thinking. Being queer is thus continually engaged in this act or attitude of building a place for the self and the beloved community. In the design and construction of place, certain patterns persist as ways we tend to shape the world.

The Names Project Quilt in Washington, DC, 1987

Celebrating the 25th Anniversary of the Rainbow Flag by stretching a gigantic flag from sea to sea, Key West, Florida, 2003

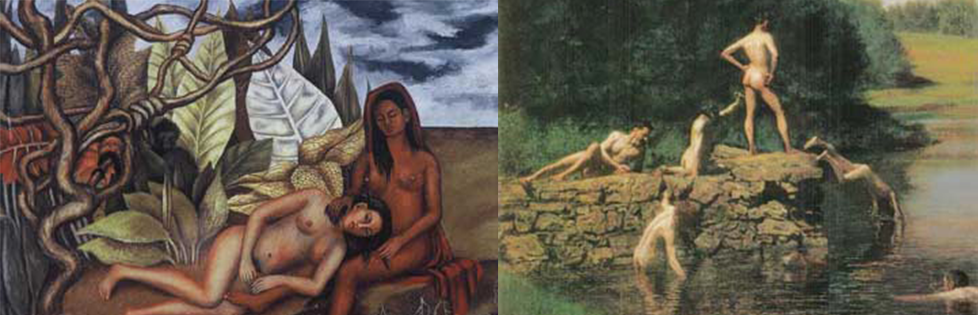

Carnival is one such pattern. We create carnival most obviously in marvelous festivities of gay pride, pride marches, the Gay Mardi Gras, the Gay Games. On Halloween, the quintessential gay holiday, we impersonate spirits and devils, satirize gender roles, mock soldiers, police, cowboys, babies, and ourselves. Judy Grahn calls Halloween “the Night of Nights for the Gay Community.”[i] Some aspect of carnival is retained in every queer space.

Carnival is exuberant celebration that incorporates both nightmare images and riotous laughter. Subconscious fears, madness, fantasies, hilarity and freakishness all take their space at the carnival. The authors of A Pattern Language describe carnival as “the social, outward equivalent of dreaming.” They write, “Just as an individual person dreams fantastic happenings to release the inner forces which cannot be encompassed by ordinary events, so too a city needs its dreams.”[ii] Queers have created carnivalesque space in which cities can dream – in steamy bathhouses, dark catacombs, and bright-lit homes that ring with music and laughter. Instead of dwelling in the suffocating blandness of heterosexist conformity, we build space where people can don masks and discard them. Women on stilts, men with beards and skirts, dykes on bikes, bears, clowns, slaves – all are brought into the mesh. Carnival honors the phantasmagoria of the subconscious. When we incorporate the carnival’s magic into the culture we create and the spaces we build, we proceed from our inmost images to our strongest connections out.

Another persistent pattern we use in the construction of gay space can be described as claiming the commons. Seemingly alone among the inhabitants of the modern metropolis, queers inhabit public space. To be queer is to enter the social and political arena, stake a claim on the commons, and redefine the commonweal. Whether lobbying parliamentarians, presenting GLBTQ issues to the local school board, shopping at the community bookstore, or participating in street festivals celebrating gay pride, being queer involves entering and creating public space.

For people who are not queer, public space might be nothing more than a journey from one private space to another. Streets appear soulless and clogged with cars. Homosexuals find it is both dangerous and exhilarating to appear in public. It takes great courage to walk down the street being an effeminate man or a butch woman. Walking arm and arm with our lover, wearing a rainbow flag, or otherwise claiming queer identity in public, we engender debate and perhaps violence. We provoke a scrutiny of social and legal limits. We claim space and create a commons – shared, contested, open space – as a condition of our lives.

Roman tetrarchs embracing, statue in Piazza di San Marco, Venice

The possibility of community resounds in queer neighborhoods. All over North America and Europe, LGBTQ people have settled in abandoned urban spaces and created, with painstaking effort, lively “villages” known for their intense street life. We have colonized rural areas and developed community institutions and services in the far North, East, South and West. People who are not queer may find community is a concept drained of credibility. Value and meaning are stuck in the private sphere, which public life leaves unexpressed. People feel unknown and unrecognized. Their personal choices, passions and heartaches stay mute and unintelligible in the forms of social and political interactions that modern life allows. As queer people, we find our inmost private being – our sexuality, our individuality, our essence – at the core of our call to community.

Building a place for being queer means that we value everyday sacredness. Ordinary acts create space for friendships. Cooking, cleaning, decorating, gardening and homemaking are examples of placemaking work that is commonly devalued. Other people may care only for money and status within institutions, but in this public world, GLBTQ people are always endangered. Our homes are homophile spaces – sanctuaries that nourish and sustain us. Creating retreats from danger, and habitats where gaiety can flourish, means valuing everyday sacredness. Simple acts of grace and kindness, a gentle voice, a carefully-made garment, a vase of flowers, a comfortable meal – all build space and place where being queer is possible.

As queer people build space in which to live, we consistently incorporate a place for the dead. “No people who turn their backs on death can be alive,”[iii] write the authors of A Pattern Language. “The presence of the dead among the living will be a daily fact in any society which encourages its people to live.” Angels fly through the opening ceremonies of the Gay Games. ACT-UP confronts the Food and Drug Administration with a die-in. The Names Project Quilt is a radical reclamation of art for human and social purposes. It comforts our spirits; it admits the enormity of our inconsolable grief. When Barbara Deming died of cancer, she left not only her writing but also a fund called “Money for Women,” which assists women in their creative projects. Cancer in Two Voices[iv] is the compelling document of a lesbian couple coming to terms with death. Though we are a people virtually without a history, deprived of human ancestors, we already have graveyards full of guardian spirits. In a society that would turn its back on death, we remember. We mourn. We accept the presence of the dead inside our call to life, to love, and to community.

Augustan funerary relief of two women, hands clasped in the gesture typical of Roman married couples, 27 BC – 14 CE

Pride is a basic pattern queer people use to create space in which to detoxify from heterosexist culture. We celebrate gay pride at rallies, dances, festivals, and by making “wild, mad, revolutionary love” (Jim Fouratt).[v] Bumper stickers, buttons and T-Shirts proclaim our pride. Pride means self-respect and more. It means we can delight in what is peculiarly queer about us. We learn to esteem the rich and complex calling that homosexuality can signify. We find joy in each other, and we find ourselves in this joy – the beauty, strength, giddy laughter, and searing prophesy I am glad of in you is also a sign of my self. We find a sense of continuity and soulfulness in the history and mythology of same-sex passion. Through pride we choose autonomy instead of shame and doubt. We prefer intimacy to isolation. We live with integrity, instead of despair. Pride also means arrogance and self-seeking. Pride can be an antonym to the humility we need to live carefully in community. But queer pride is not pride in oneself. Our pride cannot exist without finding and claiming our community. This, if nothing else, might keep us humble.

We build with pride between and alongside invisibility. Being queer involves continual acts of disclosure punctuated by spaces in which we disappear. Yet acceptance, identification and sameness offer their own pleasures and politics. Elsie Jay cautions that we lose “a whole array of invisible activities and the politics of commonality”[vi] by an exclusive focus on visibility. Queer pride is built in public space. Rally, ghetto and commercial strip are valorized by a focus on difference. Equally important are the micropolitics of sameness, through which we build home and neighbourhood outside identifiably queer space. When other alliances and identifications claim us, queer identity is slippery and cunning. Behind motherhood, class, color, shared neighbourhood, or shared environmental concerns, being queer can metamorphose into a friendly ghost. Instead of disappearing utterly, or blocking the truth of our commonality, homosexuality forms a transparency that we see through, and are seen through, and that sees us through identification, invisibility and sameness.

Even in enemy territory, we can create queer zones in the space between us. At the railway station, grocery store, PTA meeting, or doctor’s office, space is encircled, embraced, and marked off as a distinct region when we recognize one another. Finding strangers with whom to have sex is a dramatic use of this cognitive process. Aaron Betsky writes, “At its most basic, cruising is an activity not unlike that of an aboriginal walkabout, in which the world becomes a score or script that one must bring alive by walking in it.”[vii] Cruising is only a succinct expression of a function and office every homosexual engages. Whether or not we open our lives to the possibility of sex with strangers, we still bring the world alive by walking in it. In a world of ordinary people, objects and spaces, a queer person can find openings and alleyways that lead to both thrill and danger. Recognition and invitation bring the world to life. Instead of experiencing superficial interactions with a world of dead issues and fixed meanings, we find astonishment. In the space between us, gender has no more regulatory function. Wildness can flourish. There is a place for deep roots, silence and clarity. The space between us is where we find queer identity, and the whole web of mythological associations, cultural expectations, and social possibilities that come with it. Across the earth, in the space between us, the world is wakened from its slumber. Provisional, ephemeral queer zones crackle with electricity. Here, everything is possible. Mobility, fluidity and surprise characterize queer space. We are a people who cannot exist apart from one another. In the recognition by which we call each other into being, we conjure the hope and heart of a living world.

We are building, brick by brick, a world to contain us. The space we make is alive with carnival. We create community from our inmost hearts. We construct a commons in every public space. We value everyday sacredness and incorporate a place for the dead. We shape the places we inhabit with both pride and invisibility. We enter queer potentialities in the space between us.

The authors of A Pattern Language describe a view of building that has great resonance for lesbian and gay people. They write, “when you build a thing you cannot merely build that thing in isolation, but must also repair the world around it, and within it, so that the larger world at that one place becomes more coherent, and more whole.”[viii] Individually and together, we build space to be all of who we are. Everywhere, the world resists us. Yet each small act of building a place for self and community helps to create larger, global patterns. Slowly and surely, piece by piece, we make a world that has these patterns in it.

[i] Judy Grahn, 1984, (83).

[ii] Christopher Alexander et. al., 1977, (299).

[iii] Christopher Alexander et. al., 1977, (353).

[iv] Sandra Butler and Barbara Rosenblum, 1996, Spinsters Ink.

[v] Jim Fouratt, 1999.

[vi] Elsie Jay, “Domestic Dykes: The Politics of ‘In-difference,” in Gordon Brent Ingram et. al, eds, (165).

[vii] Aaron Betsky, 1997, (193).

[viii] Christopher Alexander et. al., op. cit.