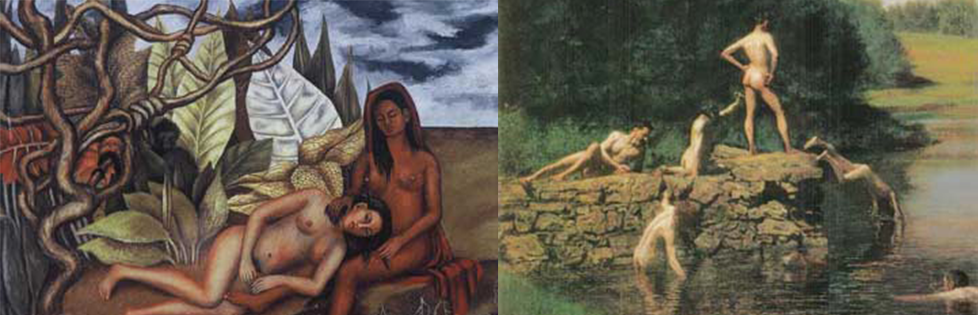

Henri Matisse, Joy of Life, 1906

Henri Matisse, Joy of Life, 1906

“Madrone Tree, from your thirsty root

feed my soul as if it were your fruit.”

– Robert Duncan[i]

Tangle of branches, thick trunks of ancient trees, smell of earth, birds shrill – this is queer space. Homosexuality is at home in the complexity, diversity, and uncontrolled energy of wildness. In a dark, old forest, sex can also be wild. There are places to hide from scrutiny, where names have no meaning or consequence. Landscaped parks with their manicured lawns are historically created to facilitate police surveillance. Queer desire is aligned with bright green growing things and the intricate fecundity of death.

Within a week of the Stonewall Rebellion, New York 1969, the first gay environmental group was formed. The group, called “Trees for Queens,” aimed at restoring a cruising area in Kew Gardens Park, Queens, New York, where extensive tree cutting and violent vigilante attacks had discouraged the presence of gay men.[ii] “Trees for Queens” envisioned the restoration of a landscape, as if in anticipation of gay theorist Alexander Wilson’s exhortation: “We must build landscapes that heal, connect and empower, that make intelligible our relations with each other and with the natural world: places that welcome and enclose, whose edges and breaks are never without meaning.”[iii] Even the name of this first gay environmental group suggests with its double-entendre that trees are for Queens – growing on behalf of Queens, in support of them – just as Queens are for trees, and so the wild world is animated, sacred, and full of love for us. “Trees for Queens” still stands as a fine example of what it might mean to queer nature. In the intervening years, many queer people have worked tirelessly to save whales and defend old-growth forests. But queer participation in the environmental movement has rarely challenged the heterosexist imperative through which natural systems are seen and conceived. What would it mean, to take homosexuality as premise and viewpoint?

Homosexuals must bring a particular sensibility to the experience of nature. Abhorred as unnatural, and alternately as bestial, castigated as primitive, and described as the strange fruit of a civilization grown too distant from the earth, we are attuned to the culture of nature. We know that nature is not a timeless essence, separate from human experience. Alexander Wilson writes, “the whole idea of nature as something separate from human experience is a lie. Humans and nature construct one another.”[iv] The natural world constructed by the modern sensibility is separated, distanced, classified by taxonomizing systems. Nature is observed from the outside, as a world of fact. It offers no omens. It is devoid of human meaning and significance. A love for nature means only a desire to watch it unfolding, or perhaps to preserve it from human intentions. As queers, we are called to experience nature differently – not just through eyes, but also through ears, nose, throat and skin. Walt Whitman writes:

“We become plants, trunks, foliage, roots, bark,

We are bedded in the ground – we are rocks,

We are oaks – we grow in the openings side by side,

. . . . We are also the coarse smut of beasts . . . .” [v]

Wildness is not something we observe, detachedly. It is home; it is a quality of the heart.

How different the wondrous world of queer nature from nature as it is experienced by “the straight mind.” Monique Wittig observes that the straight mind forms its idea of nature around an ineluctable heterosexual fact.[vi] The obligatory social and sexual relationship between men and women is the inescapable origin and end from which all phenomena are interpreted. Not only is the world ordered by a drive to reproduction and organized in breeding pairs. The whole non-human world is experienced as other. Nature is innocent, violent, illogical, helpless, endangered – in short, female. Man pits himself against it, saves it, deciphers it, fashions it to his needs.

Consider these stories:

God instructed Noah to make an ark for himself, his sons, his wife, and his son’s wives, and two of every sort of thing: fowls, cattle, and every creeping thing of the earth, a male and female of each. A great flood came, and all flesh died that lived upon the earth. Only Noah and everything with him on the ark was saved.

According to a local Coast Salish story of the flood, the people didn’t save any animals. Instead they made a huge canoe, big enough to carry every single child. The adults put the children in the canoe with all the food they had, then said goodbye, and drowned. When the water finally receded the children wound up on Mount Baker, and they started over in the Fraser Valley with nothing but what they had left in the canoe. When the children realized how many animals had perished in the flood, some of them elected to change into animals. The world was replenished by them.[vii]

Homosexual interactions are an integral part of male Orca social life. Males of all ages often spend the afternoons in sessions of courtship, affectionate and sexual behaviors with one another. Some males have favorite partners with whom they interact year after year, while others interact with a variety of different partners.[viii]

We could say that Noah had to preserve nature because he understood it in heterosexual terms. Noah had no kinship with the animals on his ark. His god had given him dominion over birds, fish and beasts, saying “into your hand are they delivered” (Genesis 9:2). Noah relied on the difference and distance between himself and the animals to secure his power over them, and so he needed to rely on breeding pairs to replenish the drowned earth. The Salish story tells of a very different world, where relationships between creatures are characterized by kinship and transformation.

Through homosexuality we are invited to live in a world ordered by kinship and transformation. The capacity for transformation, that brings us from expected modes of life to something fabulous, also brings us into alignment with the transforming world – its seasonal cycles, flowing rivers, dramas of birth and rebirth. Queer means we challenge borders and erase boundaries that prevent us from becoming one another. Sustaining ourselves and each other, we fit into a complicated web of lifeforms. We transform the established patterns, seek new habitats an abandon some, live and thrive where it seems we cannot. The extraordinary persistence of same-sex passions, throughout history and around the world, is evidence not of reproduction, but of magic.

Modern life deprives people of magic, just as it cleaves them from place. Separated from the earth and one another, they lose the capacity for storytelling, shape-shifting, tracking animals or talking to them. Nature is seen on TV, through a car window, or confined to parks. Wild is a resource and a refuge, never a home. Both the culture which rewards exploitation of nature and the resistance culture of the environmental movement are shaped by this view of nature as other. Being queer allows us to dream and begin an intimate relationship with the natural world. Queering nature may mean that instead of preserving or protecting, observing or extracting wildness, we can come home. Mythic, magic, medicinal knowledge of the wild world is part of every human culture with a sense of home. Coming home means recovering these powers in a community that includes every form of life. Home is an idea of nature that admits a place for human capacities and needs, and tells stories of human loyalty and love for plants, animals and water. With homosexuality as our premise and viewpoint, we cannot see human beings as irrevocable enemies of wildness, any more than we can see the wild world as a territory to conquer, or a series of resources to extract. To queer nature is to claim a kinship with all life, embracing the world’s diversity and interconnectedness. We are wild and wild is us.

[i] Robert Duncan, 1964, (62).

[ii] Gordon Brent Ingram, “Marginality and the Landscapes of Erotic Alien(n)ations,” in Gordon Brent Ingram, Anne-Marie Bouthillette and Yolanda Retter., eds., 1997.

[iii] Alexander Wilson, 1991, (17).

[iv] Alexander Wilson, 1991, (13).

[v] Walt Whitman, Enfans d’Adam, Bowers, ed. (61).

[vi] Monique Wittig, 1992.

[vii] Ralph Maud, 1982.

[viii] Bruce Bagemihl, Biological Exuberance: Animal Homosexuality and Natural Diversity, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1999.