Christ and Saint John. German, fourteenth century.

Christ and Saint John. German, fourteenth century.

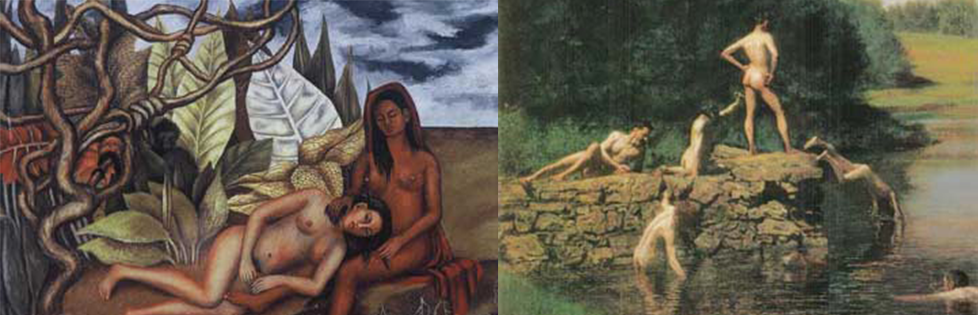

Among mentally ill people in contemporary North America, there are two common delusions. In a manic manifestation of their illness, schizophrenics often claim to be Jesus – though no one else can recognize it. Alternatively, patients in a depressed or paranoid phase of mental illness often imagine that everyone thinks they are homosexual. “Jesus” and “the homosexual” are cultural symbols that fit together, like two sides of one coin: best/worst, powerful/powerless, exalted/despised. At root Jesus and the homosexual only make sense as a single entity. They are the contemporary faces of an ancient myth: the divine child, born of the Virgin / Mother. Jesus and the homosexual are two aspects of a vegetation god who rises unalterably from the earth, only to be torn apart and devoured when the time comes. This god of green and growing things is an archetype that appears around the world, throughout time, in a multitude of myths, stories and cultural practices. Madness can be a key to the mythic dimensions of any culture. In this culture, it often points to the Tree God: Jesus/the homosexual.

Like the homosexual, Jesus is born miraculously in a most unlikely place. As a child he is exposed to threat and persecution, solitude and loneliness. Jung writes of this archetype, “The ‘child’ is all that is abandoned and exposed and at the same time, divinely powerful; the insignificant, dubious beginning, and the triumphal end.”[i] The mortal god leads a recognizably queer life. Jesus leaves home too late or too soon, gathers a band of lovers, performs miracles. He is crucified by the reigning powers and loved by a loyal underground. Betrayed and abandoned, tortured, murdered, his death is the sacrifice that brings the resurrection and the life. The meaning of his slaughter is the resurrection. His energy is life itself, and cannot be contained. Like the homosexual, he dies, he is murdered. And he continues despite his enemies. Miraculously born again and again, in the face of every punishment and prohibition, the homosexual persists.

Francisco Ribalta, Saint Francis Embracing the Crucified Christ, 1620

“Cleave a piece of wood,” says Jesus in the Gospel of Thomas. “I am there.”[ii] Jesus is the tree-god, as we can be: rooted, branching, infinitely expressive. We soar – “’scuze me while I kiss the sky” – and we go dark and deep, drawing nourishment from the underground. The tree is a sign for one, the unique and lonely individual, but underground its roots entwine with other trees, with earth and worms, and with the cyclic unity of life and death that is our world unfolding.

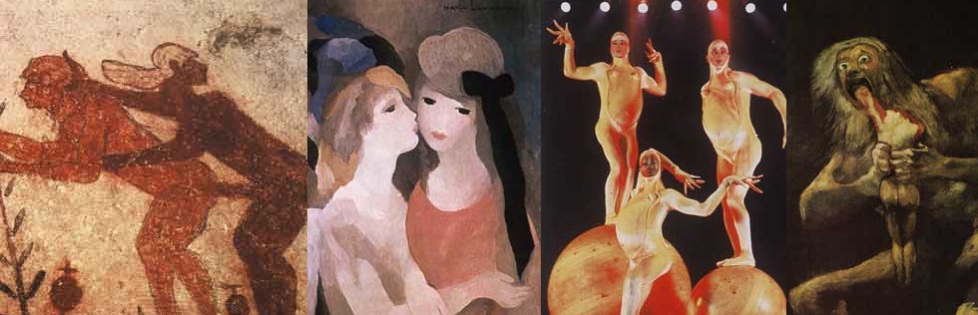

From the Taoist mountain spirit Shan Gui, through the Ancient Greek Dionysus and the Navaho Begochidi, vegetation gods around the world are androgynous. They have in common with Jesus and the homosexual a conjoining of masculine and feminine qualities, a hermaphrodism of body and soul. The androgyne symbolizes wholeness in a gender-bifurcated society, pointing to a possible future – psychic and social – and evoking a mythological past. Jung comments, “Notwithstanding its monstrosity, the hermaphrodite has gradually turned into a subduer of conflicts and a bringer of healing, and it acquired this meaning in relatively early phases of civilization.”[iii]

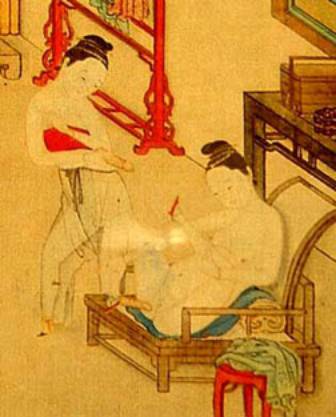

The conjoining of male and female attributes does seem monstrous in a culture based on gender difference and an economy fueled by the unpaid work of women. Is it despite or because of this monstrosity that the hermaphrodite is healer? Christ, like the homosexual, is both the phallus and the wound. Uniting these opposites in a single body, the Tree God takes us deep into the labyrinth of unconscious processes. The Minotaur demands its tribute, and the hermaphrodite also requires a sacrifice. When we embrace the monster and open its gifts, we sacrifice all the self-certainty and social approbation that gender identity affords. If we have hitherto been women, we pick up the phallus. If we have hitherto been men, we experience the wound. We become monstrous – fabulous, horrible – to everyone who stays outside the labyrinth, stuck on one or another side of gender difference. Yet here we are – a beacon of hope, a symbol of wholeness, a reminder of the repressed or forgotten moment of splitting into extremes with opposite characteristics.

Chinese women with dildos, album paining on silk, 19th C

The conscious mind is always limited, narrow in scope, constrained by personal history and social mores. If we are also the indefinite extent of our unconscious processes, we are stronger and weaker, bigger and smaller, older and younger than consciousness. Such wholeness cannot be claimed by fiat nor won through achievement. It can only be glimpsed and guessed at, lost and found, by exploring archetypes and attending to dreams.

The Tree God – as a symbol that is at once male and female, mortal and immortal, powerful and vulnerable – carries us deep into the earth and high into the sky. He is a way in, a path through, and the monster at the centre of the labyrinth. Joyous and suffering, exalted and despised, he reminds us to accept paradox and eschew resolution. As the contemporary representations of this ancient archetype, gays and lesbians suffer the scapegoating, and we carry the possibility of healing. With our miraculous persistence and our infinite complexity, we are a kind of catechism. Holding opposites without seeking compromise or the cheap solution of indifference, we pose a way to wash the world of sin.

Christ showing the wound in his side in this Florentine terracotta sculpture for above a doorway. Christ’s wound is referred to as the door, see John 10:9 “I am the door, by me if any man enter in, he shall be saved, and shall go in and out.”

Christ showing the wound in his side in this Florentine terracotta sculpture for above a doorway. Christ’s wound is referred to as the door, see John 10:9 “I am the door, by me if any man enter in, he shall be saved, and shall go in and out.”

[i] Carl Jung and Carl Kerényi, 1949, (98).

[ii] quoted by Thomas Moore, 1996, (28).

[iii] Carl Jung and Carl Kerényi, 1949, (93).