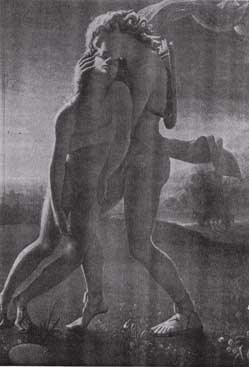

Jean Broc. The Death of Hyacinthus. Musée de la St. Croix, Poitiers.

Jean Broc. The Death of Hyacinthus. Musée de la St. Croix, Poitiers.

“Each solar flare of hatred and fear

I have survived, then sifted the ashes – a prospector.

No fire has destroyed my best and most malleable stuff.”

– Craig Reynolds[i]

Joan of Arc was a peasant girl who heard voices. In 1426, when she was 12 years old, she ran away from home and worked at an inn. Her visions increased, finally urging her to don men’s clothes and lead the armies of France. At first the army generals laughed at her, but she began to prophesy, and when her prophesies came true they let her lead the troops. The enemies of France captured her when she was eighteen, and brought her to trial for witchcraft and heresy. Joan of Arc was convicted and condemned to death. At the age of nineteen she was burned alive in the public square. She took hours to die, in terrible agony. Her screams shook the townspeople, as the smell of her burning flesh filled the air.

In 1998 two men beckoned Matthew Shepard, a gay college student, into their truck by pretending to be gay. “Guess what, we’re not gay,” said one of his attackers, placing his hand on Matthew Shepard’s leg. “You’re going to get jacked. It’s Gay Awareness Week.” The men beat Shepard’s head with their fists and a revolver. They kicked him repeatedly in the groin. When his head was so bloody they couldn’t see his face, they tied the young man to a ranch fence. Matthew Shepard hung there for eighteen hours, in the cold and dark, slowly perishing. Finally he was cut down and taken to a hospital. It took him another four days to die.[ii]

We are everywhere, it’s true, and there are societies where gender transgression and same-sex love are accepted as part of the spectrum of human capacity, available to all citizens or a chosen few. Not here. Intolerance runs deep in Western culture. The Romans persecuted polysexual pagans and reviled effeminate men, despite the prevalence of same-sex passion. In 6th Century Byzantium Emperor Justinian “ordered that all those found guilty of homosexual relations be castrated. Many were found at the time, and they were castrated and died.”[iii] In Panama in the 16th century, the Spaniards fed native people accused of sodomitical practices to dogs. Throughout Europe during the Inquisition, Christian witch hunters captured strong women and gentle men. Their fingers were crushed in vices, pieces of their flesh were torn away with red-hot pincers, and they were burned to death. In the 20th century homosexuals were imprisoned, tortured and murdered by Nazis. Those who survived the concentration camps found themselves the only prisoners not entitled to reparation. Many were imprisoned again by post-war German courts.

In the past few years, the news has carried stories of people burned alive for gender transgression, bludgeoned to death for being queer, cut to pieces, buried in sand up to their necks and stoned to death, shot, lynched, firebombed. Homosexuals are fired, driven from their homes and hunted down. Some die by their own hand. Queer youth hang themselves, blow off their heads, and OD on drugs in terrifying numbers. AIDS consumes the most precious, beloved spirits. GLBTQ people carry the burden of this suffering, whether we speak of it or not, whether we give it our attention or avert our gaze. Centuries of suffering smoke and burn inside the marrow of our bones.

What does it mean, to be so menaced? James Baldwin comments, “If one is continually menaced by the worst that life can bring, one eventually ceases to be controlled by a fear of what life can bring. . . .”[iv] The fear of suffering paralyzes identity in empty structures of disavowal. Queer people are annealed by fire. Instead of being victims of suffering, we can be empowered and enraged by suffering.

Queer people face fear every day. Death is around the corner, inside the mailbox, under the lamppost, in the eyes of the next-door neighbor. Fear keeps our hearing sharp and our eyes clear. It makes our footsteps swift and light. Suffering is our familiar, an intimate spirit at our shoulder who shapes and informs our lives.

“You’re pathetic!” teenage bullies say to all the gentle boys and strong girls. Indeed, accepting the joys and risks of queer identity includes accepting pathos as a condition of our lives. The Greek word pathos denotes suffering, and also passion, trauma, disorientation, and a visit from the gods. No wonder it is linked with queer identity. A-pathy, its opposite, is irrevocably linked with heterosexual identity in our times.

Eikoh Hosoe, Portrait of Yukio Mishima, photograph, 1961

Heterosexual masculinity is constructed by a repudiation of the pathetic self. Forsaking the arms of the Mother for the name of the Father, men forego feeling, compassion and vulnerability. Apathy is the sign of masculinity. Women are thought to have a privileged access to feeling – inasmuch as they are feminine, they are pathetic. But when they use these pathetic qualities to contrive a relationship with men, to become a commodity that can be evaluated in the patriarchal economy, they alienate their pathos in an object-identity that leaves their strength and independence unexpressed. Femininity is a product of artifice, where suffering, vulnerability and helplessness are externalized and objectified. Apathy is the secret sign of femininity, or as Marilyn Munroe sings it, “Diamonds are a girl’s best friend.”[v]

Rollo May describes apathy as the withdrawal of feeling, noting that it is linked with violence. He writes, “When inward life dries up, when feeling decreases and apathy increases, when we cannot affect or even genuinely touch another person, violence flares up as a daimonic necessity for contact, a mad desire forcing touch in the most direct way possible.”[vi] Relations between men who can never touch each other devolve to patterns of apathy and violence. Indeed it is the fear of touch – the phobic repudiation of male-to-male eroticism – that motivates so much violence between men.

When relations between men and women are drawn into the black hole of gender roles, “inward life dries up.” They cannot touch each other as human beings with passions and infirmities, capacities and needs. They can only hold the crude effigies of male and female. Apathy and violence are the telling, if not inevitable, marks of heterosexual relationship.[vii] It sometimes seems that no matter how hard and soft a man tries and a woman tries to transcend history and culture and do it differently, they get sucked into the vortex. Some humiliation they endure and some privilege they assume feeds the insatiable Hydra of sex and gender.

Homosexuals can let pathos characterize their lives and relationships. We can admit our souls into our conversations. We can admit profound tragedy, as well as transforming passion, into our hearts. Our identity as GLBTQ people is, in part, a relationship with vulnerability and loss. Suffering and death are ever-present as a possible future and a collective past. Even as we fight against the violence which threatens us, we can use suffering as a guide to claiming passionate lives and authentic relationships. Pathos is a pathway to exquisite sensibility. Being queer keeps us fiercely alive.

[i] “The Worst of It,” in Essex Hemphill, ed., 1991 (143).

[ii] see James Brooke, 1998.

[iii] Joannes Malalas, Chronographia, quoted in Boswell, 1980, (172).

[iv] James Baldwin, 1985, (376).

[v] This idea is more fully explored in my paper “sexual Subject / Sexual Object,” Resources for Feminist Research,” Volume 19, No. ¾, 1992.

[vi] Rollo May, 1969, (30-31).

[vii] James Baldwin develops this idea in his early (1949) essay, “The Preservation of Innocence,” linking impoverished gender roles with homophobia.