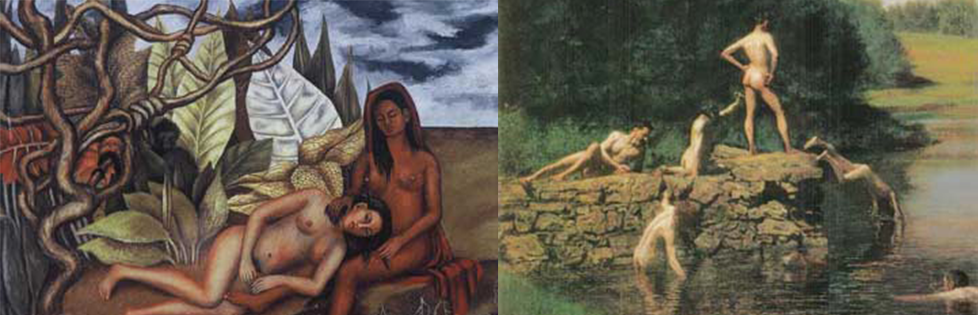

Thomas Eakins, The Swimming Hole, 1885, oil painting

Queer identity is open and fluid, still best described as love and longing. Although our bodies have been endlessly scrutinized and interrogated, we cannot be contained. In other societies same-sex sexual experience is enjoyed by one hundred percent of the population.[i]Nothing biological impedes the rampant reproduction of homosexuality. Yet we are surrounded by “science” that aims to pin it down, to make of us a minority who cannot help being what we are. Simon Levay, neuroscientist and author of Queer Science, notes that social acceptance of homosexuals hinges on the belief that we are not like them. We cannot infect, subvert or seduce them because we are born that way and they, emphatically, are not. Still there remains the lingering question of whether, perhaps secretly, or unconsciously, they really are. Homosexuality is the identity that is always possible. Queer cannot finally be fixed by difference. We can never really be said to stand opposite an other that constitutes our border and limit. We are everywhere. Ours is an identity that lurks inside, and might just rub the thighs of our fiercest enemies.

The scientists who puzzle over the ears of lesbians and the hypothalami of gay men[ii] wonder how to identify the objects of their research. How does one search for a gay gene, without deciding just what constitutes homosexuality? Is homosexuality defined by practices or desires? Does the concept include only those who publicly describe themselves as queer, or does it also comprise those who hide, deny or equivocate? Does homosexuality describe all those who engage in same-sex sexual behaviors, even in sex-segregated spaces like prison, the military, logging camps, nunneries, and girls’ schools, where same-sex sexuality is so widespread? What of those big, tough women and effeminate men who are married with children and grandchildren? In different social circumstances, would their gender dissonance be expressed in homosexuality? And then there are the many people whose same-sex relationships are not sexual, but are still passionate and primary. Is there anyone at all who can remain untouched by the fluid fact of homosexuality?

We are taught to assume that opposite-sex sexuality is the erotic preference of the normal, the majority. In the powerful 1980 essay, “Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence,” Adrienne Rich comments, “[heterosexuality] is an enormous assumption to have glided so silently into the foundations of our thought.”[iii]In fact, she notes and apparently proves with numerous examples of coercion and punishment, “heterosexuality may not be a ‘preference’ at all but something that has to be imposed, managed, organized, propagandized, and maintained by force. . . .” Without the brutal imposition of gender roles, patriarchal powers, and opposite-sex sexuality, would there be one person who did not enjoy the magic and mystery of being queer?

In the 1980’s – partially in response to Rich’s influential essay – women opposing patriarchy seemed all to be privileging and professing lesbianism. For a short time, “lesbian-feminist” became a hyphenated identity, as if one never arrived without the other. In the 1990’s “queer” achieved a similar kind of slipperiness, until the word almost managed to refuse and abandon its origins in homosexuality, and name everyone with the requisite gear. Homophobia sometimes poisoned these willful assumptions of almost-gay identities, as when lesbian-feminists called their butch-femme contemporaries unenlightened, or queer straights decried the essentialism of radical gays. Still, these are moments when homosexuality was purposefully embraced as a tool, a mask and a posture expressing social meanings. Perhaps it requires only a quixotic courage to identify oneself as queer, and then to use homosexuality as a source of knowledge and power.

Despite the fluidity of gay identities, and a suspicion that homosexuality may be “the primitive form of sexual longing,”[iv] as Freud wrote in 1899, there is no denying that being queer is a radical form of existence. Where others submit to the same dull round of repetition and reproduction, we go by preference, astonishment, the surprise of desire. Instead of vanishing into predictable categories, GLBTQ people transform established patterns, seek new habitats and abandon others, live and thrive where it seems we cannot.

Our identity-with-homosexuality is derived through our kinship with one another. We seek and recall each other. The connection is magical, for we not only see in each other a present, kindred spirit, we know each other’s past: our childhood as shy boys and bold girls who climbed trees and talked to butterflies. We know, as Harry Hay describes it, how we had to pull the green frog-skin of heterosexual conformity over ourselves to get through high school with a full set of teeth.[v] And how, if we are not yet free of it, the fairy prince or princess that we are is there beneath the skin, waiting to be awakened with a kiss. “I do not doubt I am to meet you again, / I am to see to it that I do not lose you,” sings Walt Whitman.[vi] Queer is an irrevocable bond. Ours is no subcultural community where people share a heritage and common culture. More of an interculture, we are everywhere, extending into the dominant culture in so many ways, on so many trajectories, that queer could be the glue that holds the mosaic of subcultures together. Being queer means building identity across and between us, bridging differences of sexuality, gender, race, culture and class. This form of community is chosen and achieved, not simply given. Where most communities gain their strength and structure by rejecting the other, we accept each pilgrim who announces their affinity.

We are everywhere, and yet we each have to literally fabricate ourselves and each other as queer people in hostile environments. The love which invents queer identity is nothing ordinary. It is tough and daring, gracious as a drag-queen, fierce as a bull-dagger, and just as astonishing as a woman-loving-woman, a man-loving-man. Through homosexuality we make an extraordinary leap into a sex with no other abjected and opposite.

Surely everyone has the capacity for homosexuality, but few have the courage. No one who is not – or not-yet – queer can grasp this. In 1972 Martha Shelley writes, “I will tell you what we want, we radical homosexuals: not for you to tolerate us, or to accept us, but to understand us. And that you can only do by becoming one of us. We want to reach the homosexuals entombed in you, to liberate our brothers and sisters locked in the prisons of your skulls.”[vii]Liberating this inner homosexual means something different from tasting the forbidden fruit of same-sex sexual experience. There is not really a question of whether you have or have not. There is the question of whether, from the endless possible responses to the (universal?) experience of same-sex desire, you choose love. Instead of living a bounded and defended sexual identity, being queer means having open, fluid identifications with other who are like us, or who may become so, or who may once have been so. Will Roscoe writes of the Navaho third-gender nádleehí, “the one who is (constantly) changing.”[viii]Adding a third and fourth term to the binary system of gender, queer upsets the balance and invites motion and change.

Science would like to prove that homosexuality is a permanent, pathological state. Western culture imagines us as a distinct minority. But someone completely improbable is always coming out, while others freeze up and go back in. Queer precludes closure. If the GLBTQ community has integrity, it is like a watershed. Gary Snyder describes the watershed as “the first and last nation, whose boundaries, though subtly shifting, are inarguable. . . . The watershed gives us a home, and a place to go upstream, downstream, and across in.”[ix]The queer nation has this character. It is continually taking in and letting go, the way rain swells the creeks and streams, and the river flows into the sea. Of course queer people can be just as intent as anyone else on vanishing into predictable categories: gender, sexual identity, family, race, class, nation, occupation. Yet the water is still there, singing its secrets. Being queer gives us a kinship with all life, like water. And even when ditched, diked, dammed, and filled with garbage, water will find its way down.

[i] As, for example, among the Sambian people of New Guinea where sex between men and boys is universally practiced and endowed with vital religious and cultural meanings, as studied by anthropologist Gilbert Herdt. See Mondimore, 1996, ( 15-18).

[ii] An article titled “Study Links Ears, sexual preference” in the Province newspaper (March 3, 1998, A15) describes a difference in the sensitivity of the inner ears of lesbians and heterosexual women. “Now researchers at the University of Texas, Austin, said they found the inner ears of female homosexuals have undergone ‘masculinization,’ probably from hormone exposure before birth.” Simon LeVay (1996) is the author of the hypothalamus study. David Halperin (1995) describes the appearance in San Francisco of a new gay disco called Club Hypothalamus, shortly after the publication of LeVay’s notorious study. He writes, “The point was clearly to reclaim a word that had contributed to our scientific objectification, to the remedicalization of sexual orientation, and to transform it ludicrously into a badge of gay identity and a vehicle of queer pleasure.” (48).

[iii] Adrienne Rich, 1986, (34); (50).

[iv] Sigmund Freud, letter to Wilhelm Fliess, October 17, 1899, quoted by Christine Downing, 1989, (50).

[v] Harry Hay, in Mark Thompson, 1987, (198).

[vi] Walt Whitman, “To A Stranger,” Calamus Cluster, Leaves of Grass, Fredson Bowers, ed., 1955, (105).

[vii] Martha Shelley, 1972 Gay Liberation Classic Out of the Closets Jay and Young eds, reprinted 1992, quoted in Annamarie Jagose, 1996, (40).

[viii] Will Roscoe, 1998, (45).

[ix] Gary Snyder, 1992, (271).