Perthshire, England, Swastika, 9th C. AD

Perthshire, England, Swastika, 9th C. AD

“We are your worst nightmare.”

– Queer Nation slogan

In a 2001 survey of “Canadian Perceptions of Homosexuality,”[i] people across the country were asked, “In your opinion, are homosexuals the same as everyone else?” 77% of those surveyed answered “Yes.” The notion that homosexuals are the same as everyone else (save for the unimportant little fact of who we love) was first advanced by queers in search of tolerance. Remarkably, it seems nearly to be established as a definitive statement about who we are. This hard-won form of provisional acceptance has led to the reversal of many legal inequalities. In the summer of 2003, Canadian courts made rulings that allow people of the same gender to marry one another. The U.S. Supreme Court struck down anti-sodomy laws that still criminalize homosexuality in 13 states. Yet the strategically important notion of homosexual sameness has profoundly failed to counter all the forces marshaled against us. In Canada a recent research paper estimates that homophobia results in 5500 unnecessary deaths each year.[ii] Anti-gay hate crimes have risen in recent years, becoming both more frequent and more violent.[iii] Homophobic stereotypes continue to proliferate – they are everywhere and overwhelming. The CBC news reports that intolerance is rising.[iv] In schools across North America, “That’s so gay!” is the most common insult and “Faggot!” the most brutal invective. By Grade 8, 97% of all students have experienced homophobic name-calling.[v] There is a vast and dangerous divide between the notion that queer people are the same as everyone else, and acceptance of the social and cultural difference that is homosexuality.

Homosexuality is not just the unimportant little fact of who we love. It is also the extravagant range and depth of meanings that homophobia attaches to us. Homophobia lives in each cultural image and social interaction. It shapes gender. It becomes a constituent part of family, nature, friendship, race and place. Queer meanings are also made by GLBTQ people – in our acts, attitudes, communities, cultures and histories of difference. We can see that queer is this constellation of meanings continually being made and re-made, instead of (only) an ignorable peculiarity encoded in our DNA. Homophobic stereotypes are a hated source of oppression. Nevertheless, these stereotypes preserve queer difference, proving ad nauseum that homosexuality does not fit comfortably with the dominant culture. Queer resistance transforms wounding stereotypes into empowering archetypes that help us think differently, more radically, about our social function.

Ancient Egypt, the God Bes, whose breasts gave the first drink. 1390 BC.

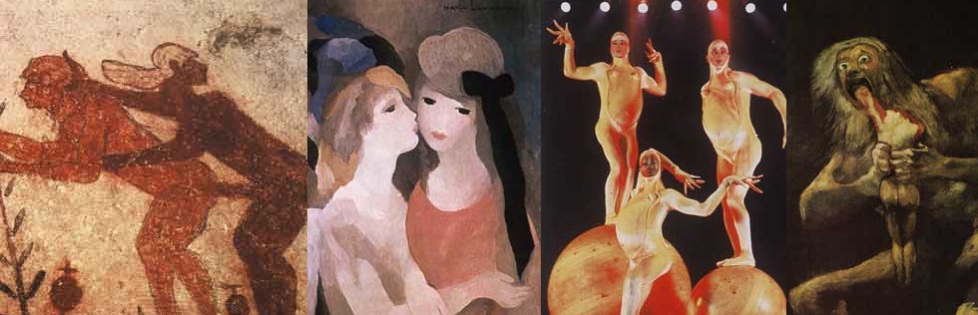

Homophobic stereotypes refer to interconnected areas of cultural anxiety. Gender is one space of great unease for contemporary society, in which we are confronted with the homophobic stereotypes of the big, butch, man-hating lesbian and the swishy, effeminate gay man. If we keep our response to homophobic stereotypes at the level of stereotypical responses, we valorize gender conformity and “straight-looking, straight-acting” gays and lesbians. There are plenty of us, and in recent years gender-conforming queers seem to have become preferred spokespeople for our communities. But if we reach through the homophobic stereotypes to embrace the submerged archetypes, we will find goddesses who point to women’s capacity for anger and vengeance, like Medusa (Ancient Greece), Sedna (Inuit), and Camunda (India). We find effeminate gods like Bes, from Ancient Egypt, whose breasts gave the first drink, or Jesus, whose wounds evoke a penetration and violation of the masculine image. Through these archetypes, we can see why the homophobes fear us. Homosexuality calls us to a world where women are powerful and men are wounded. Queer points the way to a radical revisioning of the sex-gender system. By attention to refused archetypes that shape the cultural construction of homosexuality, we can embrace gender fluidity and fight for gender equity.

The relationship with nature is another, related area of deep unease for contemporary industrial society. Here again we are confronted with homophobic stereotypes. We are called “freaks of nature” and a “biological error.” We can meet these homophobic stereotypes with plenty of evidence of homosexuality in nature, and claim a counter-stereotype – we are “born that way.” But surely it is more powerful, and more interesting, to address the reasons why the charge we are “unnatural” persists despite the evidence. Homophobes want nature bifurcated into male and female, so that the culture of nature props up the sex-gender system. Queer demands something otherwise, symbolized by the ancient archetype of gender transgression. A mask of a woman in childbirth worn by male dancers of the Yoruba tribe, or the woman who wields a triple phallus in an amulet from ancient England, point us to a way of revisioning nature. What would nature look like, if gender transgression was sought and interwoven with desire and culture, ritual and sex? If queer is nature, then nature is polysexual and exuberant. The nuclear family is not after all the inevitable model for love and breeding. The homophobes describe a natural world ordered by competition and reproductive usefulness. It is a view that would have nature mirror the social regime of contemporary society, while it justifies the pillage of an insensate earth. Queer evokes archetypes of cross-species sexuality and animal ancestors, and so a world of nature that is emotionally complex and culturally intricate. Through embracing the refused archetypes behind the homophobic stereotypes, we can create queer as a lived understanding of biological diversity. Homosexuality is a call to act and advocate for the wild.

Another area of profound social unease is the family. A host of homophobic stereotypes fall under this rubric – that we are unstable and immature, that we have dysfunctional, impermanent relationships, that we undermine the family. In the homophobes heated “Defense of Marriage” from claims by same-sex couples for equal rights, we can see the instability of the family as a social construct.[vi] The loving same-sex couple is itself an ancient archetype. Images from around the world and throughout time show a same-sex couple joined at the hips. In pursuing legal equality for queer relationships, we need not forget that the archetype has always signified something different from marriage and family life. Same-sex couples like David and Jonathan, Gilgamesh and Enkidu, Demeter and Persephone or Ruth and Naomi signify friendship, joy, twinship, passion, pleasure without possession. Securing legal recognition for same-sex relationships is important work. But we abdicate the powerful cultural meanings that inhere in our relationships when we counter homophobic stereotypes by claiming adherence to heteronormative values. The nuclear family is an unstable and dangerous construct that keeps its adherents lonely and vulnerable. It is the space where elders, wives and children are isolated and abused. Single folk are pitied and prevented from accessing the family’s economic benefits. When we are empowered by the ancient archetype of the loving same-sex couple, we can honor the alternate forms of love and belonging we create in queer community. Communal kinship patterns and partner equity are queer family traditions. We can fight against the oppressions signified by the patriarchal nuclear family, becoming advocates for the rights of children, elders, women and single people. We can honour the new kind of multi-generational, multi-sexual queer families we have made. The construction of homosexuality as a constellation of meanings that undermine the family invites us to shift the focus of queer activism. In addition to the legal fight for equal marriage rights, we can fight against the hegemony of heterosexist family values.

Tibet, 18th C, Lhamo’s saddle undercloth

Never too far behind the stereotypes that shrill against us is the persistent, terrifying spectre of the homosexual pedophile. One can hardly open a newspaper without encountering this bogeyman. We can be content to counter the homophobic stereotype of the homosexual pedophile with the blameless facts. Science proves there is no link between homosexuality and pedophilia, and suggests that children are actually much safer around gays and lesbians.[vii] And we can move to use this homophobic stereotype as a source of power and a path to insight. The pedophile refers to the ancient archetype of initiation. Zeus and Ganymede is one story of a child’s initiation to larger dimensions than the family allows. In traditional Zande culture of central Africa, warriors married boys who served them as lovers and helpers, until they became warriors, and married boys themselves.[viii] This pattern of same-sex sexuality as an aspect of initiation is repeated in cultures around the world. Will Roscoe notes that the archetype of initiation links gay experience with the shaman’s journey, which also involves submission, a shattering of the ego, and a return.[ix] Homosexuality signifies a life that is open to risk and upheaval.

The archetype of initiation might encourage us to create a new discourse on child sexuality and youth empowerment. We could be emboldened to fight age-of-consent laws that discriminate against queer youth, and laws against child pornography that are blunt and brutal weapons against queer cultural expressions. We could begin to affirm children’s sexuality and protect their gender fluidity. We could move to fight child sexual abuse where it actually, scientifically can be shown to occur – inside the patriarchal nuclear family – by fighting the society that keeps children so voiceless and oppressed. On a personal level, this could mean we become scout leaders, teachers, aunties, mentors and guardians who offer children life outside their family of origin. On a community level, this could mean building extra-familial support systems for children and youth, creating oppositional spaces and alternative cultures where children have freedoms and rights.

Zeus and Ganymede, 470 BC

Morality is another area of social unease that constellates homophobic stereotypes. In popular culture and the homophobic imagination, queer is inevitably linked with sex and violence. We can meet the ubiquitous stereotypes – prison rapists, lesbian serial killers, sex-crazed People With AIDS – with conformist counter-stereotypes. Bland, innocent, professional, straight-looking, girl-next-door homosexuals prove effective spokespeople for gay rights. And yet this effort – often undertaken at great cost to the representative specimen – seems only to feed the function of homophobia. Jerry Falwell says we are “brute beasts…part of a vile and satanic system….” Pat Robertson links us with the Antichrist.[x] We can see homosexuals as the innocent victims of unjust stereotyping, and simultaneously follow the stereotypes as maps that lead to buried treasure – the cultural meanings and social power of homosexuality.

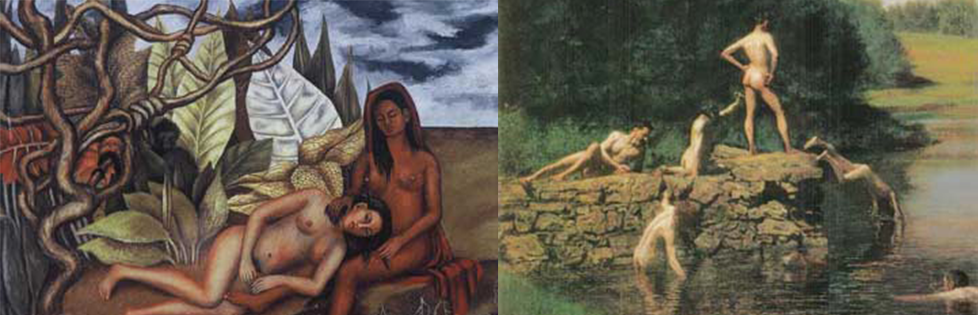

Gigantic sexual energy is an ancient doorway to the sacred. Queer sex, celebrated in the swastika image from 9th Century England that introduces this chapter, and in other ancient and prehistoric images from around the world, is an aspect of ritual worship in many cultures. Sex can connect humans with the energy of green and growing things, and to the Earth’s deep mysteries.

Carved stone pipe, Cherokee First Nation, Georgia

Among the archetypes associated with sexual morality we see how homophobic stereotypes are interwoven with racial stereotypes. Ancient and modern images show racialized others as sexual perverts, pointing to how closely queer liberation is linked with the liberation of other stigmatized identities. The exotic, erotic life of racialized others is queer; queer is darkness, slime, sin and shadow. Creatures of carnival, darkness and depravity have an ancient and enduring association with same-sex sexuality. If we reach down into the archetypal realm for our response to these demeaning stereotypes, we can be empowered by shadow archetypes. The shadow requires attention. We can attend through denial, so that evil is expressed only in pathologies and exorcised with self-righteousness. The shadow can occupy us as a cultural and political regime bent on claiming power over stigmatized others. Or we can admit the refused shadow and integrate the Beast that homophobia and racism both project onto an other.

When claiming power is claiming sameness, we have a simple reverse discourse that operates at the level of stereotype / counter-stereotype. For homosexual activists, this can mean refusing and denying darkness, just as for anti-racist activists it can mean refusing or denying homosexuality. The public face of queer is whitewashed, while racialized minorities are fetishized and sexualized inside queer communities. Homophobia in racialized communities becomes part of an anti-imperialist effort to resist racial stereotyping. Queer people of colour are multiply excluded, jeopardized and disavowed, while white queers get stuck in commodified identities – obedient consumers and producers of the repressive regime of white racial supremacy. The archetypes behind the stereotypes can point the way to a new activism, in which difference is interwoven and sought.

Empowering ourselves and our communities in ways that are informed by difference, we also honour elders and understand the past. From its first beginnings, the discourse of homosexual liberation has been woven of two parts. On the one hand, GLBTQ people have worked towards the naturalization of homosexuality, seeking integration with the whole of humanity. On the other hand, we pose and celebrate ourselves as leaders and visionaries, whose acts, habits and histories point the way to a new social order. In 1894 Edward Carpenter writes, “[It] is possible that the Uranian [(homosexual)] spirit may lead to something like a general enthusiasm of Humanity, and that the Uranian people may be destined to form the advance guard of that great movement which will one day transform the common life by substituting the bond of personal affection and compassion for the monetary, legal and other external ties which now control and confine society.”[xi] The Mattachine Society, the first ongoing gay rights organization in the U.S.A., founded by Harry Hay in 1948, was based on “a great transcendent dream of what being gay was all about.”[xii] As the society grew, it began to concern itself primarily with legal change. Hay and fellow visionaries withdrew in disillusion. Hay comments that the group became concerned “with being seen as respectable – rather than self-respecting.”[xiii] The Gay Liberation Front, founded in New York following the Stonewall uprising of 1969, tied gay liberation to peace, racial equality, and a generalized critique of capitalist society. The AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT-UP) and Queer Nation pursued gay rights through a sophisticated resistance to homophobic meanings. Die-ins of the 1980’s and kiss-ins of the 1990’s addressed the homophobic structure of physical space. Queer Nation slogans like “We are your worst nightmare” evoke the cultural power of homosexuality.

The radical current in gay activism seems to persist in brilliant but short-lived bursts that are quickly subsumed by a stronger current propelling us to seek accommodation within the dominant culture. The tension between these two currents can be productive and challenging. Joseph Campbell speaks of “two ways to live a mythologically grounded life.” He identifies “the way of the village compound,” and comments that “remaining within the sphere of your people …. can be a very strong and powerful and noble life.” But for those who are called outside the village, and who have the guts to follow the risk, “life opens, opens, opens up all along the line.”[xiv] Queers are ordinary people – mothers, waiters, judges and carpenters. Within the sphere of the village compound, we want nothing more or less than acceptance for all of who we are. And queer is a constellation of meanings that calls us outside the sphere of ordinary life. We are a way of opening to a host of unrecognized, pressing energies that are creative forces for social change.

Legally mandated civil rights for homosexuals will not dispense with queer oppressions. Legislated equality has not produced actual equality for black people in North America, though it has changed the way racism functions. bell hooks writes, “Once laws desegregated the country, new strategies had to be developed to keep black folks in place.” hooks sees these strategies as largely cultural, noting “It was easier for black folks to create positive images of ourselves when we were not daily bombarded with negative screen images.”[xv] So long as homosexuality was segregated and silent, we had some space – however precarious – of solace and self-actualization. Today we encounter innumerable mass-media representations of queer folk, endlessly reproducing the dilemma of stereotype / counter-stereotype. On the one hand, homosexuals are loveless, silly, evil, secret, savage, self-hating and socially isolated. On the other hand, they are bland, white, straight-looking, born-that-way, middle-class and sexually deprived. We are urged to internalize these options, shame queers who do not conform to the counter-stereotypes, and hold a secret sense of wrongness for whatever part of ourselves resists coercion.

Gary Kinsman notes that homosexuality is organized in relationship to all other forms of oppression and dominance, so that class, race and police oppression are manifestly queer issues. The current focus of activism on becoming citizens with equal rights creates two classes of queer people. Economically advantaged GLBTQ people benefit from legal change. Impoverished, young, queers of colour, activist, homeless and gender-transgressing queers are repudiated and ignored in the effort to sanitize and domesticate queer identity.[xvi] An activism informed by difference urges a different strategy, linking social, economic and environmental rights with individual civil rights. It requires our commitment to understanding and fighting systemic oppressions. In this view, queer difference is not a barrier to overcome. It is a joyful practice of resistance.

Claiming homosexual identity does not automatically make us politically radical. It scarcely sets us against the dominant culture, if we seek only integration, naturalization, and capitulation to its norms and values. But homosexuality is a constellation of cultural meanings that invites us to opposition. We can be a site of radical disharmony with gender roles, conventional morality, the patriarchal nuclear family, the prevailing culture of nature, and white racial supremacy. Queer in this sense is not something we are born to. It is an imaginative engagement with the cultural production of homosexuality.

If we attend to homophobic stereotypes, we see queer is not and cannot be made unimportant. As activists, we can only choose whether or not to embrace and use its importance. We can seek acceptance through representations that effect a disavowal of homosexual meanings. We can look to deconstruct and demystify queer capacities. Or we can embrace the socially constructed identity of homosexuality as an opportunity for further construction, meaning-making, and elaboration. We can use queer as a space of agency and a form of power. With our backs against the wall of heterosexist conformity, we can hear the music and dance.

[i] Canadian Press / Leger Marketing Executive Report June 22, 2001

[ii] Christopher Banks, 2003.

[iii] Byrne Fone, 2000 (418-419). See also National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Policy Institute Anti-Gay/Lesbian Violence, Victimization and Defamation at ngltf.com and a Canadian study by the 519 Community Centre in Toronto for the Department of Justice looking at the issue of violence in the LGBT community.

[iv] December 20, 2002.

[v] Gay and Lesbian Educators of B.C., 2000, Background Report (27).

[vi] A recent article in the Globe and Mail on a B.C. Supreme Court decision endorsing the right of gay and lesbian couples to marry says that “redefining marriage would amount to a massive human experiment” and admit a terrifying disorder to social relationships. Katherine Young and Paul Nathanson, “Keep it all in the family,” Globe and Mail, May 2, 2003. (A15).

[vii] Sean Cahill, Ph.D. and Kenneth T. Jones; C. Jenney et. al., 1994.

[viii] Stephen O. Murray and Will Roscoe, 1998.

[ix] Will Roscoe, 1995 (210-215).

[x] Pat Robertson from Didi Herman, 1997. Falwell quote is on the internet.

[xi] Edward Carpenter, The Intermediate Sex, from Selected Writings, ed. N. Grieg, London, 1984, quoted in Rudi Bleys, 1995, (244).

[xii] Mark Thompson, 1987 (187).

[xiii] Ibid. (187).

[xiv] Joseph Campbell in conversation with Michael Toms, 1988, (23-24).

[xv] bell hooks, 2001, (76-77).

[xvi] Gary Kinsman, 2003.