“Lezzie!” “Faggot!” “Dyke!” “Queer!” In the schoolyard, bullies hurl their worst insults. Young people who identify as gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, gender-variant or queer (GLBTQ) are socially isolated and unsafe. Queers are the most frequent victims of hate crimes, and schools are the primary setting for hate-crime violence. A recent Canadian survey reports that nearly half of queer-identified youth have attempted suicide at least once. One in six is beaten so badly that they require medical attention.[i]

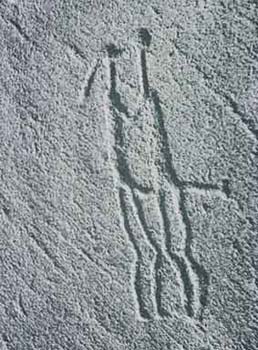

Sweden, sacred rock carving of two men fucking, early 1st millenniumSweden, sacred rock carving of two men fucking, early 1st millennium

Same-sex passions are everywhere and ordinary, throughout nature and around the world. Yet homophobia endures. Despite the hard work of queer activists, the new visibility of queer artists and entertainers, and the fact that many, if not most people in North America now have someone in their lives who is openly queer, negative stereotypes proliferate. Fearsome and terrible notions of homosexuality still seize the popular imagination, and find continual expression in popular culture. Queer youth are endangered. Elders are isolated. Fear infects the lives and shapes the deaths of GLBTQ people.

How does homosexuality incite such hatred? How do queer people come to pose such a radical threat? In cultural terms, homosexuality is evidently much more than the ordinary, enduring fact of same-sex sexual preference. Homophobia impresses each queer life with a bone-deep knowledge that our difference holds a terrible variety of meanings, a bewildering complex of allusions and associations. On September 13th, 2001, two days after the terrorist attack on the United States, the Reverend Jerry Falwell blamed gays and lesbians for making god mad. The Christian Right says “the gay agenda is the devil’s agenda.[ii] ”Sexual lasciviousness, disease, treason, cowardice, the abuse of children, the contamination of blood – every imaginable evil is linked with homosexuality. Henning Bech comments, “there is no evil that the homosexual cannot embody.”[iii] We are accused of acting against god, family values, the national interest, evolutionary logic. “We’re talking about the deconstruction of American society,” says Christian Coalition of Georgia Leader Sadie Fields.[iv]The symbolic figure of “the homosexual” is a monster. And though this bogeyman is far removed from our manifestly ordinary lives, we are forced to live with the consequences of its construction.

The strategy of the contemporary civil rights movement has been to counter homophobic stereotypes by asserting a profusion of counter-stereotypes. We protest our innocence, and claim that homosexuality is natural, ordinary and uninteresting. What would happen if, instead, we acknowledged our fearsomeness, and explored the power that contemporary culture invests in homosexuality? Instead of always deflecting the blows that homophobia metes out, we could learn, as in Eastern martial arts, to “go with the blow.” It is a way of using the energy the enemy gives us

We can ask what it means to acknowledge that homosexuality is associated with the end of the world as we know it – not to uncover meanings hidden inside us, but rather, as a kind of “tuning in” to the allusions and associations broadcast by the cultural phenomenon of homosexuality. To examine what homosexuality signifies, we can listen to the noise it makes. How does homosexuality resonate throughout the culture, in connection with other cultural constructs like gender, nature, family and race? What does this imply for those of us who aim and claim to “be” homosexual? This book explores these questions.

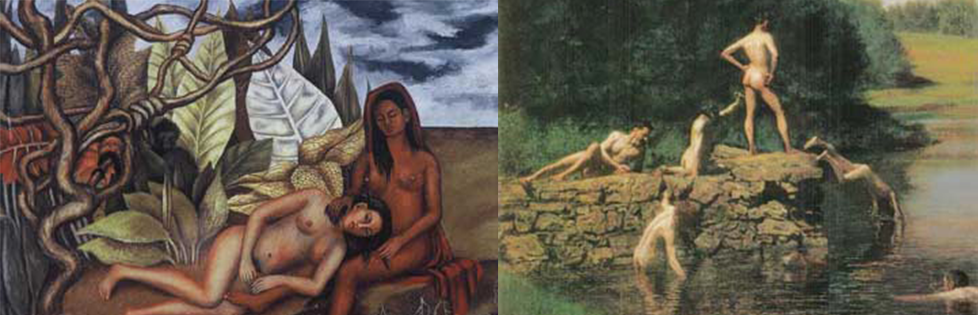

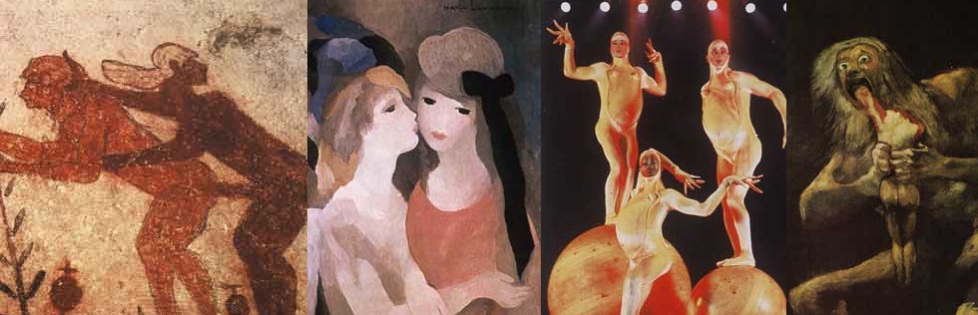

In these writings I draw on contemporary scholarship and include historical information on same-sex passions, but Orientation is not a scholarly work. I am an artist who has worked for twenty-five years with images, patterns and archetypes. I approach the question of queer identity with an artist’s attention to meaning and metaphor. I find a kind of magic in those notions of homosexuality that can be described as homophobic stereotypes. Stereotypes are undistinguished, trite and obvious images that keep us locked in empty nothings. Archetypes are powerful, living symbols that link us to myth and history. Yet both can be described in the way Carl Jung speaks of archetypes: both stereotypes and archetypes are “involuntary manifestations of unconscious processes,”[v] or “the thoughts that think you.” So often, stereotypes that oppress queer people open into archetypes. Vengeful witch, stone butch, pedophile, androgyne, wild man, clown – such figures have rich historical antecedents. They express aspects of human experience that claim symbolic presence in the myths and dreams of many cultures.

The archetypes, stereotypes and images in which we are enmeshed are an enormous burden. I see them also as a gigantic opportunity. The net of meanings that surrounds us as queer people can be seen to link us with myth, history, and the capacity to transform society. In this book my point is not to interpret, nor even less to untangle, this web of association. I aim not to explain and dispose of stereotypes, but to amplify them. I approach the multi-layered meanings that accrue to homosexuality through reflection and poetry as well as critical analysis. In the overall structure of the book, I travel through the alchemists’ five basic elements, looking at archetypes and stereotypes that resound in Earth, Fire, Air, Water and Space. My informing metaphor is the alchemists’ effort to transform self into numen, dross into gold. In contemporary Western culture homosexuality signifies transformation – personal upheaval, social disruption, and spiritual change. We can refuse these meanings, and the journey, tasks and attainments that are suggested by a capacity for transformation. We can advocate for ordinariness, decline each special meaning, and look to the normalization of homosexuality for safety to live our mundane lives in peace. Or we can amplify the symbolic resonance of queer identities, explore and expand our capacities, and use these gifts to change the culture that would confine us.

Jung writes, “Not for a moment dare we succumb to the illusion that an archetype can finally be explained and disposed of. . . . The most we can do is to dream the myth onwards. . . .”[vi] I write here to “dream the myth onwards,” and I write as queer person. I speak of a “we” which history has constituted – we are the homosexuals. History constructs the meta-category of homosexuality, thereby allowing us to claim identity across differences. Multiple, diverse and often antagonistic differences of sexuality, gender, race, culture and class are embraced by the category of homosexuality. In this sense, there is a global fellowship of homosexual people. History, language and culture present us with a stark differentiation between “us” and “them.” Homosexuality requires of its advocates a kind of “strategic essentialism”[vii] – we can use our identity with others to build alliances and create belongingness. In this sense, homosexual identity can be understood as an important social and historical aim, as well as an analytical tool. Stuart Hall writes that identities “are about using the resources of history, language and culture in the process of becoming rather than being: not ‘who we are’ or ‘where we come from’, so much as what we might become, how we have been represented and how that bears on how we might represent ourselves.”[viii] In this book I write of choosing queer identity, and of using the history, language and culture that construct homosexuality to create new forms of being and new worlds. When I write of being queer, then, I am not writing of particular GLBTQ lives. Rather, I am giving attention to a cultural construct and locus of meaning that seems rich in content and capacity.

Queer, as I describe it here, precludes the closure implied by fixed and singular notions of identity. We each in queer community owe parallel allegiances to multiple identity positions. And people are forever whirling and turning from one sexual orientation to another. In recent years writers have explored the conflicted identities of lesbians who sleep with men, or transsexual men in gay relationships who become female and thereby straight. Certainly whenever anyone loudly claims to “be” heterosexual, we can hear the tiny, screeching voice of an inner homosexual. And homophobia is so fundamental to our culture, it is constitutive of any identity we lay claim to. Gay or straight, we cannot live without an inner homophobe who wants to manage our options and strangle our dreams. As a homosexual, I am meant to be marginalized and excluded from majority culture, and yet I also participate in telling the stories and constellating the identity by which homosexuality assumes its meanings. When I write of “we, the homosexuals,” I embrace the identity in all its complexity. I also call on what is queer in all people, however they conceive of their sexual orientation. Queer is, but is not only, the part of everyone that opens to the possibility of same-sex love. In this book, queer means the part of I that is an other, the one we glimpse in dreams. Bent on social transformation, queer is vulnerable, yet willing to risk. Queer is guided by inner yearnings instead of community consensus. Being queer is not inevitable, but it is possible, no matter whom we love. When I write “we,” I mean to invite everyone who prefers to embrace these potentialities.

Lesbian, homosexual, queer and gay are all beloved words. I use them all, with their rich social and mythological associations. I mean to include the strong critiques of gender and patriarchy that come with the name lesbian. I mean to draw on the bio-medical model and the claim to minority status that come with the name homosexual. The oppositional stance signified by queer is central to my project. Queer may be the proper name for what I value in the cultural meanings and lived experience of homosexuality. I resist a wholehearted adoption of the term, however, because queer has a lack of specificity that means the word is too easily detached from its homosexual roots. I enjoy in the word gay a name that is specifically and strategically homosexual. It is ebullient – the word conveys the joyous exhilaration of being gay. Gay is our own word for ourselves. It was used by queers as a secret code word for at least a century before gay activism pushed it into social parlance. Gay has a relationship with gender that is fluid and inclusive. And gay is historically linked with liberation, visibility and community. I hope that bisexual, transgender and gender-variant people, along with gays, lesbians, queers of all description, and those heterosexually-identified people who are “straight not narrow,” will find in this book an invitation. In my view, any identity one assumes and speaks through can be productively queered. This book is written to honour the aspects of anyone’s life that can be explored and enjoyed through attention to the social construction of homosexuality. Being queer, as I see it, is nothing any homosexual is born to. It is a possibility we may – or may not – invent and discover, as we live with the socially reviled, yet culturally crucial concept of homosexuality.

Though this book is a very personal meditation, I imagine some ways it might be useful to others. For those engaged in a personal journey of growth and discovery, I hope this opens a dressup trunk to play with. I find each chapter or aspect of Orientation can form a place for meditation and inspiration. I like to use, try on, enjoy and discard various facets of homosexuality as a personal pathway for spiritual growth. I have used the ideas and images in this book in workshops where I involve participants in creating artwork that explores affinities with homophobic stereotypes and submerged archetypes. We then discuss the relevance of these ideas and images to personal life and political activism. This allows people to approach issues of identity and social construction in a fresh way, perhaps less formulaic than what is offered by contemporary academic or political discourse on queer potentialities.

Creative people may find, as I do, that attention to the images and archetypes surrounding gay and lesbian identity can inspire new work, sometimes in unexpected ways. For example, the section of this book I call “Water,” with its flow of images and meditations on the nature and culture of water, informed my recent sculpture, Water Dream / Water Memory. In a Vancouver park I worked wit a community to build a 400-foot long dry creekbed following the path of a buried stream. The environmental sculpture incorporates river rocks, riparian plants, and rocks engraved with a poem about water. The concept involved creating a tiny complex piece of nature to serve as habitat. The work proceeds directly from thinking nature through a queer point of view. It echoes an intricate, unseen and refused (queer) nature; it explores connections between blood, tears, constrained complexity (homosexuality), and a buried stream; it asks people to pay attention to the intersection between self and world (in a way that both evokes and proceeds from being queer).

Caffyn Kelley, Water Dream/Water Memory, details of environmental sculpture

I draw deeply on the well that is queer and gay/lesbian studies. If I have a contribution to make here, it will be because my viewpoint is different. I do not write with the scholar’s need to prove and explain, but rather, with the artist’s aim to suggest and intuit. Like practitioners of cultural studies, I assume that homosexuality is socially and culturally constructed. And I find in this fact an untapped vein of gold. Contemporary Western culture has no great myths. It tells no stories of magic and transformation. But it talks ceaselessly of homosexuals. In a world that is contemptuous of sacrament and mystery, there is still one way to evoke a place of secrecy, depth, gigantic risk, erotic power, the quality of being “impossible.” There is being gay. Instead of witches, warrior-women and virgin mothers, there are lesbians. Instead of fools, martyrs, water-spirits and vegetation gods, there are gay men. Homosexual people can be seen to represent the mythic narratives and potentialities of contemporary Western culture. The constructed identity of homosexuality holds this journey inside it, like a blossom could hold an apple – not an essence, but a possibility – a whisper, a promise, a blueprint, an inner impulse. If we can seize hold of the rich variety of meanings that inhere in queer identities, we can assume these powers.

For readers whose passion is for social justice, I hope this book enlivens the conversation. I am myself a passionate local activist. I have explored the implications of my view for political action throughout the book, and most particularly in the concluding chapter, “Stereotypes, Archetypes and Activism.” In addition to the contemporary focus on civil rights, I would recuperate gay liberation, and continue to use queer as a social project. In recent years, gay activists have pushed for social tolerance of our difference. Their work has had profound effects. I feel safer in my community and in my skin because of the legal and social reforms achieved by the civil rights movement. My gratitude is balanced by an awareness that hate crimes have risen. An openly hostile “family-values” coalition has achieved significant political presence. Among the small majority of people who constitute civil society, prejudice may only be more secret. Fear and hatred of gay and lesbian people may even be characterized by denial. The wish for our annihilation must be expressed politely, as a wish for our assimilation: “They are no different,” or, “It makes no difference to me.” The space between the toleration of difference and the annihilation of difference is easily bridged. Audre Lorde cautions, “Advocating the mere tolerance of difference . . . is the grossest reformism. It is a total denial of the creative function of difference in our lives.”[ix]

This book is written to affirm and nourish queer difference. Love and laughter open our hearts to our capacities. Images and archetypes help us find the places of creativity and power in our history, community, lives and identities. As we carry the displaced needs and wishes of an entire culture, the otherness we are can form a dialectical opposition to the society that oppresses us. Without difference, there is no dialectic, and no possibility of social transformation. While we cannot escape or transcend homophobia, we can choose a way of conceiving self and world that is apposite and opposite. By inventing, exploring, preserving and proclaiming our difference, we enable creative change in society and in each heart.

In my view, homosexuality can be so much more than a sexual preference, a psychological condition, and a minority status. Queer is a way of being, a Dao, that can be practiced. It is a joy and a calling. Homosexuality allows us to redefine the scope of our souls. It is a way to embrace and repair the world. With every image, pattern and archetype we build into the web of nature and society, we make ourselves and the world more queer, and so at once more fabulous, more complicated, and more whole.[x]

[i] see 1994 study by the U.S. Department of Justice; 1994 study by the U.S. Department of Justice; “Being Out – Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Youth in B.C.: An Adolescent Health Survey,” McCreary Centre Society, Vancouver, 1999; Pierre Tremblay, University of Calgary study on suicide and gay youth.

[ii] See Didi Herman, “The Gay Agenda is the Devil’s Agenda.”

[iii] Bech, 1997, (186).

[iv] Sadie Fields, quoted in MacLeans’, March 29, 2004, p. 26.

[v] Jung, Carl G. and Carl Kerényi, 1949, (72).

[vi] ibid., (79).

[vii] In Gayatri Spivak’s phrase. Stuart Hall, 1989, writes, “where would we be, as bell hooks once remarked, without a touch of essentialism… or what Gayatri Spivak calls ‘strategic essentialism’, a necessary moment?” (472).

[viii] Stuart Hall, ed., 1996, (4).

[ix] Audre Lorde, 1984, (l11).

[x] David Halperin (1995) describes Michel Foucault’s informing notion of homosexuality: “Homosexuality for Foucault is a spiritual exercise insofar as it consists in an art or style of life through which individuals transform their modes of existence and, ultimately, themselves. Homosexuality is not a psychological condition that we discover but a way of being that we practice in order to redefine the meaning of who we are and what we do, and in order to make ourselves and the world more gay; as such, it constitutes a modern form of ascesis. Foucault proposes that instead of treating homosexuality as an occasion to articulate the secret truth of our own desires, we might ask ourselves, “what sorts of relations can be invented, multiplied, modulated through [our] homosexuality….”