Fernand Khnopff, pastel drawing, 1889

“Only the shallow know themselves.”

– Oscar Wilde[i]

“Invert,” the word derived from the Latin in (in) and vertere (to turn), names the action of turning inward. And this is not any ordinary self-reflection, but an in-turning that turns things upside down and inside out. The noun “invert” names one who is transformed by inversion – who else but the homosexual.

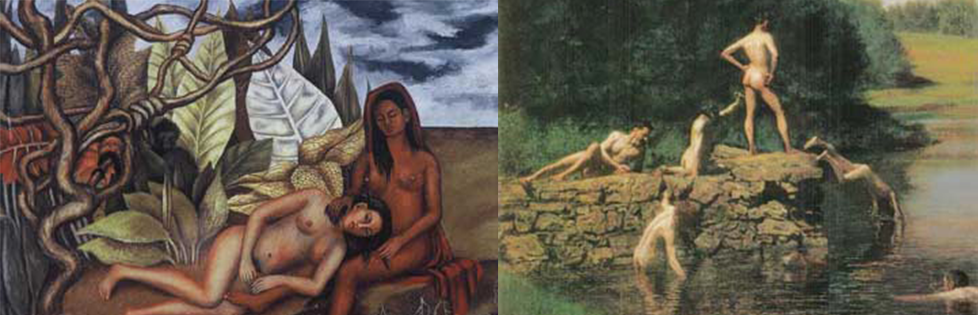

Being queer is a call to inversion, an in-turning that leads us to quiet places in nature, where still, clear water upturns the known world. And if a wandering youth is thirsty for a taste of this inverted world, where all is soft, deep and unfamiliar, he might catch sight of his own watery soul. Narcissus finds an image reflected in the dark surface of a hidden pond – a self who he thinks is someone else – and he falls in love. The boy he yearns for is not the familiar image of himself he could find in a bright-lit mirror. It is a surprising, unfamiliar self – fluid, secret, soulful.[ii]

Narcissus’ love for the boy he finds deep in the forest, in the untouched pool of still, clear water, can be described as an inversion of the ordinary self-consciousness that can be acquired through mirrors. Psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan describes the mirror-stage as formative of self-consciousness. In the brittle plane of a mirror, a child sees only surfaces. Reflections there say nothing of bodily fluids, organic needs, and interior functions. All the eye perceives in the mirror is an “I” who appears to be whole, complete, and independent.[iii]While still “sunk in motor incapacity and nursling dependence,” a child overcomes fear by assuming an identity with the insentient object he or she appears to be, in the mirror. The “I” is formed in this mirror-stage as a self-consciousness that is separate and self-sufficient. “I” forgets fear and danger. “I” repudiates knowledge of time and space, where we are interwoven with an intricate web of life. Yet no one has blood and breath apart from this. So “I” must stay trapped in paranoid structures. “I am” always poses (historically, linguistically) as a self-sufficient entity, disavowing identity with what it lacks. All that is other becomes viewed as inessential. The subject inhabits a negatively characterized world of objects. Jacques Lacan describes this “mirror stage” as a misrecognition that comes to characterize the ego in all its structures. He calls it a “knot of imaginary servitude that love must always undo again, or sever.”[iv]

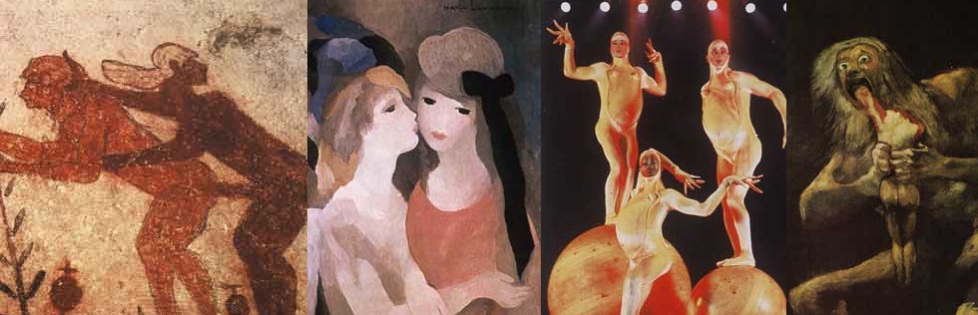

Heterosexuality is one way to keep this self-sufficient self-consciousness going. “Man” and “Woman” are other and opposite, separate, distinct, composed of rejected attributes, negatively characterized. In relationship “he” and “she” function as mirrors to one another, offering up superficial images and reinforcing paranoid disavowals of fear and mortal destiny. Within the patriarchal social structures that surround and confound us, “woman” acts as object to his subject. She guarantees his power by her service. He stays trapped in the crippling misrecognition of his self-sufficiency. And perhaps he is also trapped in unconscious envy of her privileged access to feeling and to powerlessness.

Loving someone of the same sex, we cannot stay in comfortable assumptions of difference. We recognize our identity with our lovers. We see and want our double, our self. But this is not the mirror-self, appearing whole, complete, and independent. We catch a glimpse of the fluid, soulful self – weeping, urinating, defecating, hungry, thirsty, readily shattered, impossibly needy – in our lover’s eyes, arms, and asshole.

When two women or two men love each other, no female (or feminized) object stands opposite a male (or masculinized) subject. No one guarantees his power by her service. Paul Monette describes “the challenge two men fucking [make] to the slave laws of the patriarchy. . . . the exchange of power, the wild circle of top and bottom.”[v] Two men together make a “wild circle” of subject and object, dependence and independence, separation and merging, passivity and power. Being queer makes it possible to acknowledge strength and weakness, authority and abjection, in a wild erotic round. Difference does not derive from indifference. Objective insufficiency need not be cast into an abyss inside self-knowledge; it can be used, played with, cared for and loved as an aspect of both self and other.

Persia, watercolour, Wrestlers, 1684

The anxious self-certainty of ordinary self-consciousness can only be achieved by the transcendence of objectivity. It is the objective truth of separation and independence that guarantees one’s insufficiency and need. An alternative consciousness lives in the world of objects: organic, endangered bodies; trees and rain; food and water; books and music; blood and skin. Grief, hunger, love and laughter illuminate – at times with unendurable clarity – the gap between individual and indivisible life. Instead of claiming transcendent self-certainty through the repudiation of risk and dependence, being queer means we can listen to uncertainty and live in cognizance of incompletion. The endangered self, wanting what it does not have, can only be loved through inversion.

In unique relation with the dynamics of self-consciousness, queer people can claim rich capacities and sensibilities. We can want more than the self-sufficient subject could ever dream of not-having. We can acknowledge abject need without surrendering all power. Despite and because of our objective limits, we can take a chance on love.

[i] Robert Byrne, ed.

[ii] This idea is derived from Thomas Moore, 1992.

[iii] Jacques Lacan, 1977, (1-7).

[iv] ibid. (7).

[v] Paul Monette, 1992, (144).